in the movies

(An aside before I get going today: today in my Intercultural Communication class, we watched Gung Ho and Rick Overton, Ralph in Groundhog Day had a small but briefly important role in it. He’s 7 years younger and they barely say his character’s name but once or twice so while I noticed his name on the IMDb page, I didn’t recognize him until a good way into the film. He doesn’t have any great thematically central dialogue like “That about sums it up for me” but his getting injured on the assembly line does make for a key moment in the themes of that movie.)

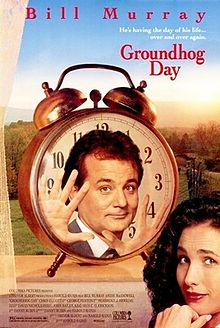

Today, February 12, is the anniversary of Groundhog Day’s original release. So, let’s look back.

Jerry Adler and Ray Sawhill—apparently, it took two authors to review one movie—at Newsweek, 8 March 1993*, for example, note the importance of Bill Murray’s casting in the film. “Acting a scene, Murray’s face registers a sequence of emotions as precisely as a galvanometer,” they tell us. They continue:

Between expressions the needle always falls back to zero, which is what makes it possible to watch him for virtually every second of a 103-minute-long comedy about claustrophobia and tedium. With a hotter personality—Robin Williams, say—the movie would be unviewable.* and unless otherwise specified, all references below are also from 1993, obviously.

”Bill Murray is the man we love to love while he’s being hated,” Richard Alleva tells us in Commonweal, 26 March.

Caryn James in the New York Times, 14 March, says “only a cad as engaging and commonsensical as Mr. Murray could keep this film going. Other actors would have made Phil abrasive or sappy as he reveals a good heart.”

Roger Ebert, in his updated review, 30 January 2005, says, Murray transformed the film into “something sublime, while another actor might [have] reduce[d] it to a cloying parable.” He continues:

The Murray persona has become familiar without becoming tiring: The world is too much with him, he is a little smarter than everyone else, he had a detached melancholy, he is deeply suspicious of joy, he sees sincerity as a weapon that can be used against him, and yet he conceals emotional needs.

As for the premise, Janet Maslin in the New York Times, 12 February, calls it “a sitcom-style visit to the Twilight Zone [that] starts out lightweight but becomes strangely affecting.

The aforementioned Caryn James suggests—wrongly, I’d say—that Groundhog Day “sounds like a dopey kids’ comedy. Instead, it’s a dopey adult comedy, a major hit with audiences and critics starved for romance and mindless escapism.”

Ebert, in his original review, called Groundhog Day “basically a comedy, but there’s an underlying dynamic that is a little more thoughtful.” He called it “lovable and sweet” and implied (but didn’t state outright) that it was original rather than a “formula” comedy. But, he only gave the film 3 stars originally.

When he later revisited it, he upgraded it to 4 stars and began his new review like this:

"Groundhog Day" is a film that finds its note and purpose so precisely that its genius may not be immediately noticeable. It unfolds so inevitably, is so entertaining, so apparently effortless, that you have to stand back and slap yourself before you see how good it really is.Certainly I underrated it in my original review; I enjoyed it so easily that I was seduced into cheerful moderation. But there are a few films, and this is one of them, that burrow into our memories and become reference points. When you find yourself needing the phrase This is like "Groundhog Day" to explain how you feel, a movie has accomplished something.

I was talking to Michael Schulman, the New York Times reporter I met in Woodstock, again yesterday and he asked me if the movie gets old. Others have asked me that as well. Strangely—or maybe not—it hasn’t. Perhaps that’s because of what Ebert is referencing here. The film has a precision and ease that makes it eminently watchable

Ebert concludes his revisited review like this:

What amazes me about the movie is that Murray and Ramis get away with it. They never lose their nerve. Phil undergoes his transformation but never loses his edge. He becomes a better Phil, not a different Phil. The movie doesn't get all soppy at the end. There is the dark period when he tries to kill himself, the reckless period when he crashes his car because he knows it doesn't matter, the times of despair.We see that life is like that. Tomorrow will come, and whether or not it is always Feb. 2, all we can do about it is be the best person we know how to be. The good news is that we can learn to be better people. There is a moment when Phil tells Rita, “When you stand in the snow, you look like an angel.” The point is not that he has come to love Rita. It is that he has learned to see the angel.

Kenneth Turan at the Los Angeles Times, 12 February, says, “There is a romantic innocence about [Danny Rubin’s] concept that survives the overreliance on Hollywood schtick that weighs down the film’s first part and makes us believers by the close.” Countering that, perhaps, Ebert suggests (in his original review), “Murray is funnier in the early scenes in which he is delivering sardonic weather reports and bitterly cursing the fate that brought him to Punxsutawney in the first place.”

Kenneth Turan says the film “may not be the funniest collaboration between Bill Murray and director Harold Ramis, and it doesn’t have a chance of being the most financially successful. Yet this gentle, small-scale effort is easily the most endearing film of both men’s careers, a sweet and amusing surprise package.” He also says,

Rubin’s story has more warmth than you might anticipate, as well as its own kind of resilience, and having the gruff Murray (rather than some more fuzzy and cuddly actor) endure a change of heart makes the softer emotions easier to accept. With MacDowell as the pleasant foil, Murray turns “Groundhog Day” into a funny little valentine of a film. It won’t overwhelm you or change your life, but after all the more obvious laughter is over, it may just make you smile.

Considering Ghostbusters total box office was nearly $300 million, and Groundhog Day would end up making around $70 million, Turan’s right about Groundhog Day’s financial prospects, but there wasn’t much for the studio to worry about, of course.

(Turan’s wrong about Groundhog Day being able to change your life, of course.)

As Jeffrey Ressner recounts in the Chicago Tribune, 2 May, Groundhog Day’s test screenings did quite well. “During November’s screening,” he writes, “the only noise Columbia execs heard was the jingling of cash registers.” He explains:

Shortly after the movie ended, NRG staffers passed out the cards and later calculated a “score” based on answers from the survey’s first two questions—“What was your reaction the movie overall?” and the all-important “Would you recommend this movie to your friends?” According to Columbia, the numbers for “Groundhog Day’s” first test fared even better than final results for “A League of Their Own.”

A) I assume that is a great baseline for comparison there at the end; the phrasing implies that A League of Their Own was maybe the highest rated screening they’d had up until that point. B) I still try to get to test screenings whenever I can and those first two questions are still the same two questions. Then they get into more specific stuff, rating certain actors or the direction, or the music. They ask you to list your favorite and least favorite scenes, anything that confused you. My problem is that right after seeing a movie, I tend to like it. My negativity usually takes a little time to kick in. So, I’ve probably rated some movies at screenings higher right then than I would after putting a little thought into it. It occurs to me, though, that maybe studio execs don’t particularly care about reactions that come later. They just want to know what will get butts in the seats.

In addition to good screening scores, Groundhog Day would also benefit at the box office because it was rated PG. Elaine Dutka explains in the Los Angeles Times, 22 March:

Columbia Pictures has revamped its ad campaign for the Bill Murray hit “Groundhog Day,” focusing on the cuddly little rodent himself…In Hollywood, PG is in.

”Any smart businessman can see what we must do,” Columbia Pictures Chairman Mark Canton informed the theater exhibitors attending the ShoWest convention earlier this month. During an era of rising production costs, he said, family oriented films give more bang for the buck.

Productions costs seem to always be rising, of course, and family-oriented films still do well. Like with Groundhog Day, I think it helps—and I’m not saying anything profound or original here, I’m sure—if the film works well for the kids and the adults on separate levels and there’s some shared middle ground as well. I saw The LEGO Movie tonight, and most of the audience was adults—though, to be fair, it was an 8:30 P.M. showing—but kids in the audience certainly enjoyed it as well. When I saw Groundhog Day on the big screen in Woodstock, that first day when there were more kids in the audience, the kids and the adults both enjoyed it. The adults had probably seen it more than once but a certain nostalgia kicks in, and if it’s the first time their kids are seeing it, there’s something meaningful there as well.

(Nostalgia for playtimes past probably accounts for a lot of the adult audience for The LEGO Movie as well (or maybe it was just a bunch of AFOLs).)

Kids did like Groundhog Day, of course. For example, 12-year-old Jonathan, quoted in the Los Angeles Times, 4 March, calls the movie “funny… Not funny like a ‘Kindergarten Cop’ movie. Or ‘Home Alone.’ But… this one has more of a message and not as many gags.”

But, Dutka continues:

Social as well as fiscal factors are feeding the family film trend. Hollywood is being targeted for excessive sex and violence…[Keep in mind what’s following Phil’s weather report on PBH at the beginning of the film: “entertainment editor Diane Kingman looks at sex and violence in the movies.”]…Recessionary times create a market for uplift and diversion. Equally important, the baby boomers are finally growing up.

”The audience that worshiped Martin Scorsese and headed for ‘Mean Streets’ is now living Steve Martin’s life in ‘Parenthood,’” observes William Morris senior vice president Joan Hyler. “That doesn’t’ mean that they won’t be going to the art houses, but as parents they both relate to, and have a need for, a broader range of films.”

Dutka also mentions the box office, specifically. “Family films,” she explains, “are also more likely to generate the ‘repeat’ business that separates mere hits from blockbusters.

“Kids don’t mind watching the same movie four or five times,” notes Warner [Brothers’ Bruce] Berman. “Especially since Chuck E. Cheese, ice cream and toy stores are also at the mall. These movies also drive our licensing and retail store businesses. Out of our ‘Batman’ Animated TV series, we developed a whole new line of toys.”

Alas, there was no Groundhog Day line of toys, no Phil Connors action figure with Punxsutawney Phil accessory. No Nancy Taylor that dances like she’s listening to polka music when you push a button on her back. No Larry who does far more than just hold a camera and point it at stuff. No Zacchaeus with falling action. No Buster with choking action. No newsvan with secret missiles that reveal themselves with the push of a button… What? It would totally have something extra like that if it were real.

When Bill Murray’s other 1993 release, Mad Dog and Glory came out in March, Groundhog Day was “one of the top grossing movies in America” according to David Friedman, Los Angeles Times, 6 March. Knowing the film was a success, Friedman explains (quoting Murray, of course), made Murray “not just loose. Goofy… You know, it’s nice knowing you’re doing your job well. It makes you—well, it makes me, anyway—goofy.”

It was, indeed, a success. The Los Angeles Times reported, 17 February, that Groundhog Day was the number one film its first weekend, making $14.6 million on 1640 screens (for a per-screen average of $8934). Keep in mind, just by inflation rates, that’s like $21 million, and it was February, not exactly a big movie month. For comparions, though, this past weekend is a bad example unless you skip past the number one movie--The LEGO Movie, which made $69 million. Second place, The Monuments Men, which includes among its stars none other than Bill Murray, made $22 million, and third place, Ride Along made only $9 million.

The weekend in question in 1993, by the way, had Groundhog Day at $14.6 million, Sommersby second at $9.9 million, Homeward Bound at $8.2 million, Alladin in its 14th week at $6.7 million, and Loaded Weapon I at $6.1 million.

$14.6 million, by the way, was the reported budget for Groundhog Day so, ignoring the cost of marketing and whatnot, everything after that first weekend would be profit.

Today’s reason to repeat a day forever: to design and build a line of Groundhog Day toys. And, perfecting the prototypes would surely be enough to get free of the time loop, so the world would be a far better place afterward with kids everywhere reenacting Phil’s journey of redemption.

Comments

Post a Comment