you have to add some twists and stuff

Interestingly, just as started The Sixth Sense tonight, I notice a link to an io9 article—“The Cultural Curse of Knowledge and Movie Spoilers”—that doesn’t deal with The Sixth Sense’s twist and how everybody knows it, but makes a good point about how those of us who know because we’ve seen the film (or any film with a twist, for that matter) almost can’t help but SPOIL it for anyone and everyone without much deliberation or planning. We just do it, because, as Inglis-Arkell (2014) writes in the piece, “People who have some piece of knowledge, whether it's technical or incidental, have a hard time thinking from the point of view of people who don't have the same knowledge.”

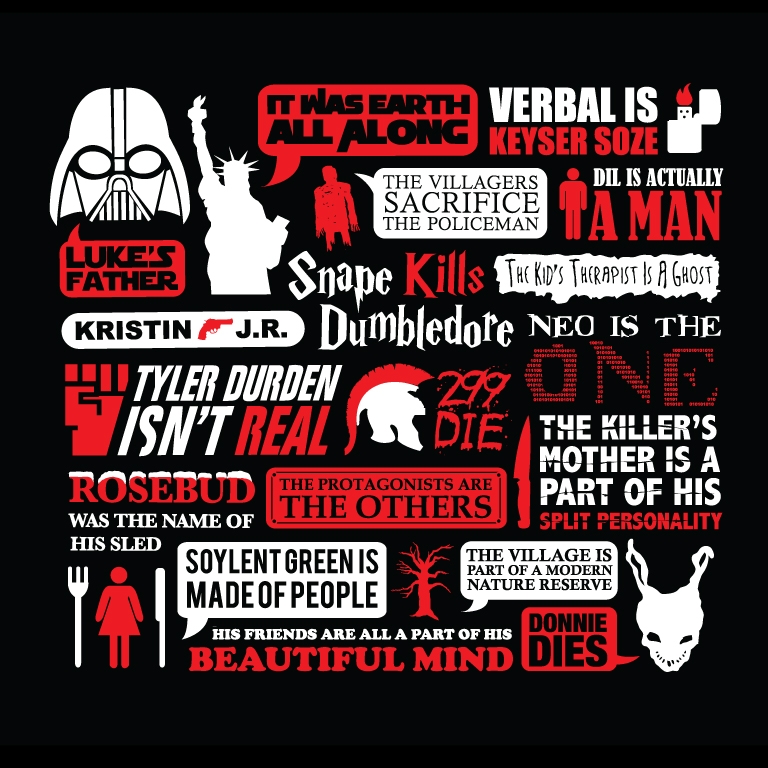

For more SPOILERS, by the way, here’s a nice shirt from Threadless:

The Sixth Sense is on the right, about a third of the way down: THE KID’S THERAPIST IS A GHOST. That’s the big third-act twist. The twist that made M. Night Shyamalan a household name. The twist that “blind-sided” Roger Ebert (1999) even though “The solution to many of the film’s puzzlements is right there in plain view, and the movie hasn’t cheated, but the very boldness of the storytelling carried [him (and all of us)] right past the crucial hints and right through to the end of the film, where everything takes on an intriguing new dimension.” Mendelson (2014) says, “The Sixth Sense was a genuine cultural phenomenon, and it turned Shyamalan into Hollywood’s newest would-be golden boy.”

It was only later that Shyamalan became more of a joke than a box-office draw.

Shyamalan knew—when he made The Sixth Sense—how to craft a twist. He even explains, within the confines of the story, how stories need twists.

Malcolm Crowe (Bruce Willis) tells a story to Cole Sear (Haley Joel Osment) and he is not a good storyteller…

Malcolm: Once upon a time there was this young prince and he decided that he wanted to go for a drive. And, he got his driver and they started driving, driving, driving, driving a lot. And, they drove so much that he fell asleep. (beat) And, then he woke up, and he realized that they were still driving... This was a very long trip—Cole: Dr. Crowe. You haven't told bedtime stories before?

Malcolm: Not too many, no.

Cole: Well, you have to add some twists and stuff.

Malcolm: ‘k, some twists. Like what kind of twists? Give me an example.

Cole: Maybe they run out of gas.

Malcolm: They run out of gas. That's good, ‘cause they’re driving, right?

A story is just a collection of twists, things that happen so it isn’t just a straight, boring line from Point A to Point B. Some twists are bigger than others, of course, but it’s still all twists. In this case, they are Shyamalan’s chosen twists, presented for our benefit. Stewart (1982) writes, “The artifice of the storyteller, his control of the mode of production of the story, holds the audience within the story’s world” (p. 35). A good director, a good writer—in this case, both being Shyamalan—invites us into his “story’s world.” Backtracking to The Ring for a moment, Stewart describes how, essentially, we in the audience serve as “victims” to the story:

…the audience rarely knows more than the victim of the story. This victimization of the reader [or viewer] is particularly clear in those scenes in the written horror story where the reader is presented with a letter to be read at the same moment, within the same temporality, as it is read by the character. (p. 39)

Similarly, that first time Rachel Keller watches the cursed tape, we see it along with her. We experience it as she does. The Sixth Sense operates a little differently as far as Cole’s story goes—we don’t see the ghosts (though we do hear the one at the birthday party) until we hear Cole says his famous line: “I see dead people.” We are situated with Malcolm in this story. We know what he knows, which, given the twist, means we simply never have all the information we need, because, like Malcolm, we can only see what we want to see. Well, technically, we only see what Shyamalan wants us to see. The point is our point-of-view is deliberately narrowed so that we get the bits and pieces we get and nothing more. We fill in the gaps with our imagination. I saw a comment—I think it was on IMDb—about Malcolm and how he should know he’s a ghost because no one ever interacts with him. But, the whole point to the ghosts in The Sixth Sense is that they simply don’t consciously operate like we do, like they did when they were alive; they get the edited bits and pieces like we do. Ghosts are like we the audience, getting a scene here and there and filling in the gaps in between. We don’t see characters using the restroom, for example, but that doesn’t mean we assume that it never happens; it just isn’t important to the plot so it is left to the side. For Malcolm and the other ghosts in The Sixth Sense, their entire existence is like this, like they only live in edited movies put together by other people.

Klecker (2013) describes movies like The Sixth Sense as “meticulously designed narratives that force the audience to participate actively and lead up to the final mind-boggling plot twist” (p. 120). Like I said above, Klecker points out that the twist here has “become part of mainstream culture and… not just specialized knowledge within the circle of film buffs” (ibid). Klecker quotes Bordwell (2006) citing Dixon (2001) regarding where the horror genre has gone since The Sixth Sense; Bordwell writes:

The audience is confronted with one violent spectacle after another, devoid of any context or explanation. The human has been reduced to the level of mere agency in these mechanistic spectacles, which have been created to cater to the ever-diminishing attention spans of image-saturated viewers. Contemporary audiences don’t want complexity, they want hand-holding simplicity, in which every step of the narrative construction is heavily foreshadowed and plays out in a nondisruptive manner. Because of the wide variety of new and competing media, more has become less. We no longer have the time to become intensely engrossed in a complex narrative structure, or the desire to be surprised or challenged. (p. 122)

The big blockbusters get simpler and simpler, more spectacle than depth. There are always exceptions, of course, but, when the fourth Transformers film, IGN reports, just passed $1 billion worldwide, it makes sense.

The Sixth Sense does not exist solely for its twist. Klecker (2013 calls the film, “initially—as straightforwardly Hollywood as they come” (p. 130). It’s a generic enough supernatural thriller with some great acting raising it higher than it has a right to be, until it gets to that ending. The ending alters what we’ve come to know so far. Klecker explains:

…at a first viewing, most mind-tricking films develop a classically narrated plot. The illusion of film as reality is kept intact; viewers are immersed in the story and are emotionally involved. Due to the twist ending, though, which calls into question everything that was believed to be true before a reviewing in the light of the unexpected disclosure, a second viewing will have a very different emphasis... the viewer’s attention shifts or extends from the narrated to the narration itself. (p. 140)

Indeed, watch something like The Sixth Sense a second time and it is a far different film; you pay attention to different things. Hell, the second time, you probably just sit there trying to discover all the clues you missed before—that we never see Malcolm actually open the door the basement, that no one interacts with Malcolm, that he clutches at his wound when he gets emotional and breaks the window at the store where his wife works, that we don’t actually see how he breaks that window (I assume it was not a physical break but a psychical one), that Malcolm may remove layers of his outfit but never actually wears another outfit… and so on. You sit there and you kick yourself for not noticing things that now seem obvious.

What’s interesting, though, is that a third viewing, or a fourth, or a fifth (or what have you), can bring you back around to something else, back to Cole’s story, to Malcolm’s story, to the emotional elements over the plot devices that take precedence in light of the twist. This is a story about failure—Malcolm failed one of his patients and feels guilty, so he needs to help Cole, Malcolm also (effectively) failed at his marriage, since his wife thought she came second to his work (and, probably, despite what he tells her at the end, she did come second; it may only be in retrospect that Malcolm realizes she was more important than the work he put before her), Lynn Sear is—she likely believes (and others certainly suspect as much)—a failed mother, doing all she can for her troubled son but failing to help him when he most needs it. But, then Malcolm helps Cole figure out what to do about the ghosts and things get better, for everyone. Anna Crowe may still miss her husband, but she is in the process of moving on with her life. Life goes on beyond what we see on the screen, just as life continued between the various scenes before.

The story may be a fiction, but that doesn’t mean that it is an entirely self-contained thing, that its characters do not live beyond what we see. Cole Sear will go on to help other dead people. Malcolm will go… wherever dead people go. Lynn will work her two jobs and take care of her son. Anna will not forget Malcolm, but she will let go of her grief—which we see symbolically as she literally lets go of his wedding band as she sleeps.

The characters keep going… but so do we, after the credits roll, so we are no longer privy to their lives, because we have our own lives to live.

Works CitedEbert, R. (1999, August 6). The Sixth Sense [Review]. http://www.rogerebert.com/reviews/the-sixth-sense-1999Inglis-Arkell, E. (2014, August 10). The Cultural Curse of Knowledge and Movie Spoilers. io9. http://io9.com/the-cultural-curse-of-knowledge-and-movie-spoilers-1618755315

Klecker, C. (2013). Mind-Tricking Narratives: Between Classical and Art-Cinema Narration. Poetics Today 34:1-2. pp. 119-146.

Mendelson, S. (2014, August 6). 'The Sixth Sense' Made M. Night Shyamalan Into Hollywood's Last Spielberg. Forbes. http://www.forbes.com/sites/scottmendelson/2014/08/06/the-sixth-sense-made-m-night-shyamalan-our-last-original-blockbuster-director/

Stewart, S. (1982). The Epistemology of the Horror Story. The Journal of American Folklore 95:375. pp. 33-50.

Comments

Post a Comment