wasn't my war, colonel. just cleaning up the mess.

Watching Rambo: First Blood Part II for the last time--I like to toy with the idea that after watching any of these movies for multiple days I will retire them from my viewing repertoire--it strikes me that I haven't had much that was actually negative to say about this film. Sure, it represents an attempt to rebuild American hegemony symbolically, and a manipulation to reconstruct the myth of Vietnam, but it's just so damn fun.

So, I figured I'd end this week of Rambo by looking backward, see where Rambo came from. I've mentioned David Morrell, author of the novel First Blood. I've even talked here and there about differences between book Rambo and movie Rambo. But, why does Rambo even exist?

Wilder (1990) presents us with a story--I'll just provide the beginning of it:

A young boy is raised in a patriotic Christian culture to love god and country; to believe "Thou shalt not kill." At the age of 18, not yet old enough to drink or vote, he is given a "choice": go fight in an unpopular war very far away, openly resist and face imprisonment, or leave the country in exile. Unable by virtue of social class, he enlists and begins a basic training calculated to override his lifetime of values and make him into a killer. He is then sent half way around the world alone, without a support group, on a one year tour of duty in a situation so horrifying he will never be able to truly share the experience with those who did not participate. He is thrust into a war, where he does not know who the enemy is, where the lines of battle are, or what the objectives may be, because the enemy is everywhere, the lines do not exist, and the objectives are hopeless. (p. 198)

To continue that story, after being trained to kill, he kills. In some circumstances, he does worse. But, we don't win this war and when he comes home, he finds himself shunned, spit on... Let's let Rambo tell it (from First Blood):

Nothing is over! Nothing! You just don't turn it off! It wasn't my war! You asked me, I didn't ask you! And I did what I had to do to win! But somebody wouldn't let us win! And I come back to the world and I see all those maggots at the airport, protesting me, spitting. Calling me baby killer and all kinds of vile crap! Who are they to protest me? Who are they? Unless they've been me and been there and know what the hell they're yelling about!

Or, maybe that never happened...

http://www.creators.com/opinion/david-sirota/the-legend-of-the-spat-upon-veteran.html

http://www.boston.com/news/globe/editorial_opinion/oped/articles/2005/04/30/debunking_a_spitting_image/

http://www.slate.com/articles/news_and_politics/press_box/2007/01/newsweek_throws_the_spitter.html

Maybe that is more revisionism. More of Anderson's (2013) rewriting of American myth. Sure, we lost, but maybe that loss doesn't really mean anything unless a) we get to blame someone, i.e. the hippies and b) we get to really turn them into assholes. Reality doesn't matter when we can rewrite the story, rewrite the myth. Were vets treated badly? Sure. Were there hippies waiting in every airport and bus station to spit on them? No. But, there were not Communists hiding all over the country, either, but we ran with the story for a while, too. What matters is the narrative. And the narrative said, boy goes to war, boy is damaged, boy returns to be shunned.

Another part of the story is like it is with Rambo--boy goes to war before he's probably held down a regular job, maybe before he's been with a girl (let's just assume heteronormativity for the moment; Americans certainly assumed it at the time... or we can add "or a boy" at the end of this sentence). He's trained to kill, "to destroy the village to save it" (Wilder, 1990, p. 198). And then he comes back home. Maybe he's not damaged, but he's also not particularly skilled. And, he's competing with boys who weren't drafted, boys who didn't run off to fight the red menace, "Johnny get your gun" and all that. Patriotism and army training can only take you so far when you're back in the real world. Like John Rambo, you can't hold down a job. Like Martin Riggs, like John Matrix, maybe the one thing you were ever good at was killing people.

Shunned or not, you don't fit in anymore. This is who Rambo is.

And, he lives in a world where there is violence both abroad and at home. Morrell puts the initial inspiration for First Blood in a CBS broadcast that showed a firefight in Vietnam and National Guardsmen marching on rioters in an American city. Morrell (1988/2000) writes:

It occurred to me that, if I'd turned off the sound, if I hadn't heard each story's reporter explain what I was watching, I might have thought that both film clips were two aspects of one horror... The juxtaposition made me want to write a novel in which the Vietnam War came home to America. (p. viii).

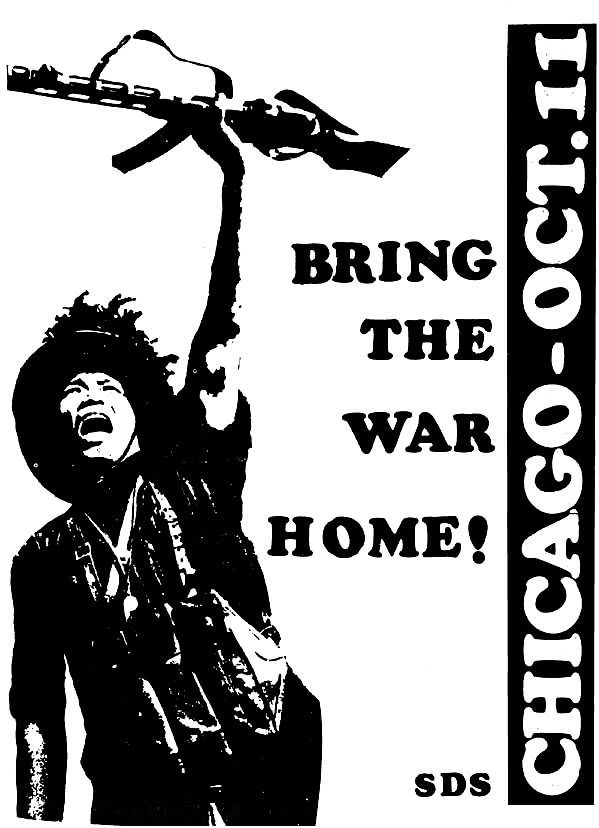

I'm not sure which firefight or which riot Morrell saw that night, but his story reminds me of the 1968 "police riot" in Chicago, and the "Bring the War Home" pamphlet that brought protesters and dissidents back to Chicago a year later.

Black (2012) argues that, between the police riot and the days of rage, the "antiwar movement, which had potential for 'legitimate protest' before, was becoming a 'youth rebellion'" (p. 29). The "Bring the War Home" pamphlet reframed the idea of Vietnam, of the antiwar movement, of America. Morrell sought to do something of the same... on paper. He writes: "...maybe it was time for a novel that dramatized the philosophical division in our society, that shoved the brutality of the war right under our noses" (Morrell, 1988/2000, p. viii).

His "catalytic character" was Rambo, no first name (in the novel), a man "embittered by civilian indifference and sometimes hostility toward the sacrifice he made for his country" (ibid). The name came from the convergence of poet Rimbaud (who Morrell was reading at the time for a graduate school French class) and Rambo apples his wife brought home from the store. "A French author's name and the name of an apple collided, and I recognized the sound of force," Morrell writes (p. ix). He cites an incident in a "southwestern American town" in which a group of hippies were "picked up by local police, stripped, hosed, and shaved... and driven to a desert road, where they were abandoned to walk to the next town, thirty miles away" (ibid).

It took ten years for the novel to make it to the screen because of "the mood of the seventies." Morrell explains:

America's involvement in Vietnam had ended badly, and feelings about the war were bitter. The few films that referred to Vietnam (Coming Home, for example)) reflected that attitude. Then came the eighties. Ronald Reagan was president. He promised to make America feel optimistic again. The defeat in Vietnam seemed far behind. (p. xi)

Morrell's ending, with both Rambo and Teasle dead, was left behind. Too depressing. There had to be a winner, even if Rambo did end up in prison over it.

A few years later, Rambo would be set loose in Vietnam. Morrell had nothing to do with that story, but because of a contractual detail, he got first dibs on writing the novelization. He also wrote the novelization for Rambo III. The original novel had made it into classrooms, onto reading lists. The controversy and violence in the sequels pulled it out, off. But, Morrell doesn't object to the films. "Their level of action is nowhere as extreme as current examples of the genre" (p. xiii, and I assume this line is from the 2000 rewrite), he says. "Politics aside, they're a lot like westerns or Tarzan films..." (ibid).

Let's not get started on those racist, colonialist, patriarchal, anglocentric stories. Instead, Rambo.

Morrell doesn't object to where his creation went over the decades since First Blood was published. So, I don't see why I necessarily should, either.

He compares the book and the movies to two trains, "similar but headed in different directions" (p. xiv). Finally, he compares Rambo to "a son who grew up and out of his father's control" (ibid). Morrell's son. America's son. He's still family, no matter how many foreigners he's killed over the years. When the fifth Rambo movie comes out--currently, it's going under the title of Last Blood and there were rumors a few years back of a science fiction turn adapting The Savage Hunter into a Rambo story--I will go see it. Plenty of people will. Probably not as many as saw Rambo: First Blood Part II in theaters. But, enough. And, Rambo's story, far outgrown beyond Morrell's novel, will come to an end.

Until any of us rewatch the movies again, of course.

Works CitedAnderson, M.C. (2013). How to win the Vietnam War: More Rambo. West East Journal of Social Science 2(2), 11-22.Black, R.E.G. (2012). The solution to violence in the streets: Framing the 1968 Democratic National Convention Police Riot in the National Consciousness. Unpublished manuscript. Department of History, California State University Los Angeles, Los Angeles, California.

Morrell, D. (1988/2000). Rambo and Me [Introduction]. In First Blood (vii-xiv). New York, NY: Grand Central.

Wilder, C. (1990). Wounded warriors and the revisionist myth. In A. Berger (Ed.), Media U.S.A. (197-205). New York, NY: Longman.

Comments

Post a Comment