insect or man, death should always be painless

(A note, in case you are just joining the Groundhog Day Project: the phase 2 description above suggests that I am watching one movie seven times, but for this month, I am not doing that. Unless you count slasher films as one long film split into weird little chapters… which isn’t that bad a way to think about it, I suppose. But, even then, it is not seven times but 33 times this month.)

Saul Bass opening titles—always a good thing.

A specific date and time as we come into the window to find Marion Crane and her lover. The Final Girl was not a thing yet, but this movie lets us know first thing that this seeming lead character is not a virgin. There’s no hint of a killer and already some moral grey areas. The film, with its Saul Bass opening credits, it’s black and white (when color was an option, mind you), and the question of respectability (and morality) in the relationship on display, seems like a setup for a film noir more than the horror films that would borrow tropes from it in the future.

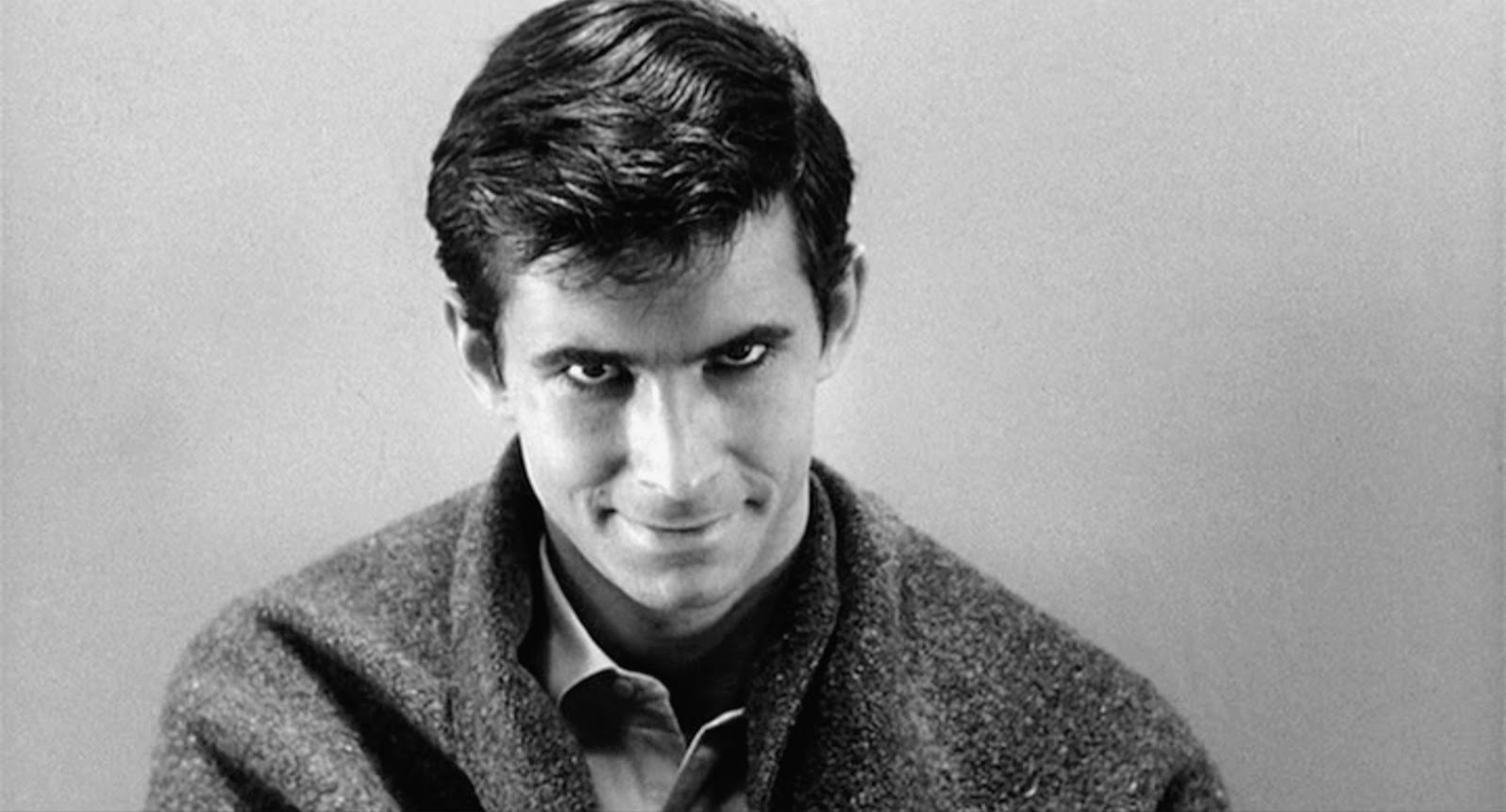

The film in question is Psycho, of course.

And, now, in less than 10 minutes, we’ve seen the lead in her bra twice, and while it was white before (and she and lover did talk about having a respectable relationship and even getting married), it’s black now, with the envelope full of cash on the bed. Having watched Pretty Woman so recently, the images reminds me of a prostitute, and I’m sure that isn’t an accident. Marion Crane is painted as a morally questionable woman from the start. Yet, we are with her; she’s our protagonist... for now.

And I find myself just watching the film for a couple of reasons. First, there isn’t much to say about Psycho that hasn’t already been said. Hitchcock has been studied time and time again—I even wrote a paper about The Birds during my first stint in college. Back when I was hoping to major in something related to film and wanted to make movies. I suppose I wouldn’t mind making movies still. Hell, I made one, sort of, this past summer.

Many have written about the shower scene. Cinematically, it’s still probably one of the best sequences in film, and the reason Hitchcock is considered a master at this stuff. Something I haven’t seen much written about—and that isn’t to say that it hasn’t been, just that I haven’t seen it—is some other camera stuff Hitchcock does. I mean, the quick cuts in that shower scene are cool and all, but I rather like something he does right after. After showing us the drain and the close up on Marion’s eye, then zooming out slowly, the camera looks around the room. And, I choose that word deliberately—looks. Though there is no one there to be looking around, the camera moves like someone looking around. Just as earlier Hitchcock put us inside Marion’s mind—and her seemingly imagined conversations of those she left behind—by keeping the camera on her face as she drives, with only the occasional cutaway to the road ahead, here he places us inside that room. We’ve just witnessed this murder and can do nothing about it, and we are looking around, maybe thinking about how that newspaper on the table might be evidence. In a way, we are allowed to survey the scene just as Norman will only moments later, take it all in not as deliberately as a film usually might show such a scene but almost casually, spontaneously. Then, the camera turns to the window, in time to hear Norman up at the house, discovering his mother. And we watch him stumble down the stairs to come see what his mother has done.

Speaking of stumbling down the stairs, the private detective falling down the stairs after “mother” stabs him is another great shot...

What I think I really want to say today is that, thought I felt I must include it in this month of slasher films, and though Clover (1987, 1992) ties Norman Bates to the other killers in the various slasher films, Psycho is not really a slasher film. The deaths are all a bit too sudden. There’s none of the stalking that is ubiquitous in the slasher genre.

Speaking of Clover (1992), she suggests that in watching slasher films—and this holds true for Psycho—

We are both Red Riding Hood and the Wolf; the force of the experience, in horror, comes from “knowing” both sides of the story. It is no surprise that the first film to which viewers were not admitted once the theater darkened was Psycho. (p. 12)

Thomas (2010), describes the scene in the theater:

Psycho was famous all along for having paraded its own originality—if you’ve got it, flaunt it—inside and outside the purlieus of Hollywood. Hitchcock in life-size cardboard cutout, pointing at his wrist watch, and intoning that “No one... but not one... will be admitted to the theater after the start of each performance,” was also changing when we looked as well as how we looked and what we saw. (p. 86)

Clover continues:

Whether Hitchcock actually meant with this measure to intensify the “sleep” experience is unclear, but the effect both in the short run, in establishing Psycho as the ultimate thriller, and in the long run, in altering the cinema-going habits of the nation, is indisputable. In the current understanding, horror is the least interruptible of all film genres, and this fact itself bears witness to the compulsive nature of the stories it tells. (p. 12)

Calling Psycho a thriller may be more appropriate than calling it a horror film. Except, I wonder just how shocking and horrifying the revelation of Norman’s mother in the basement would have been in 1960. Coming out of a conservative time in America, and slipping into a world where sex was openly discussed. Take Peeping Tom and Psycho together, and it’s obvious, something in the postwar world was changing. The slasher genre was being birthed out of changing gender roles, changing politics, and changing ways of thinking about differences (not just gender) between human beings. It’s important to note that Norman is specifically not classified as a transvestite at the end of this film. He embodies both an incomplete version of himself and an incomplete version of his mother, but the psychosexual fury doesn’t come from one or the other, per se, but rather from the conflict between them.

Works CitedClover, C.J. (1992). Men, Women, and Chain Saws: Gender in the Modern Horror Film. Princeton: Princeton University Press.Thomas, P. (2010). “Her Fine Soft Flesh.” Film Quarterly 63:4. pp. 86-87.

Comments

Post a Comment