men and women can't be friends

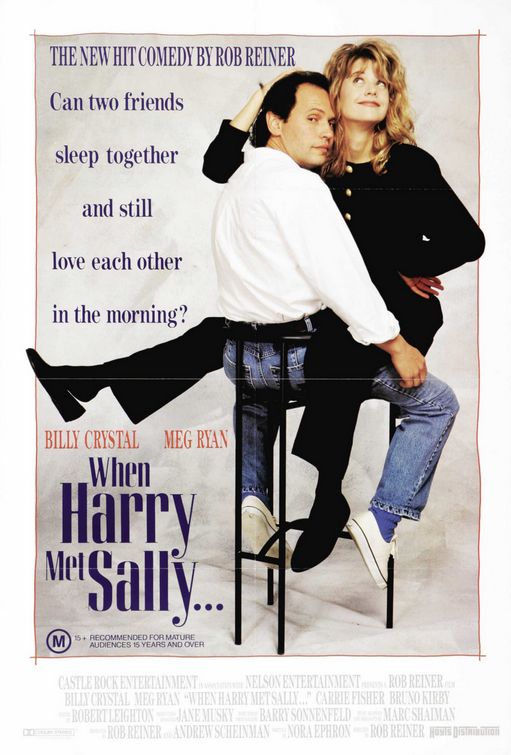

It’s been a long while since I watched When Harry Met Sally all the way through. Didn’t see it when it came out in theaters, saw it sometime in the 90s on cable. Last fall, though we watched the beginning of the movie in Comm Theory class when we went over Altman and Taylor’s Social Penetration Theory. In short, it’s about the multilayered onion of our selves—think of that conversation between Donkey and Shrek in the first Shrek movie; we get close to new people by disclosing information starting with the outer layers. But, I’m sure communication theory will get more coverage later in the week.

For now, my thoughts on When Harry Met Sally:

I considered starting this entry with a line about how I had a lot of female friends in high school... except my school was so small, you could be friends with everyone. Plus, I’m not sure it disproves Harry’s theory.

Anyway, as far as romantic comedies go, I’m starting here with a sort of deconstructionist one. I’m not a fan of romantic comedies most of the time. Too much shallow optimism for me, and I’m too much of a pessimist and cynic to believe in love at first site (which is not a part of When Harry Met Sally) or the “meet-cute.” Hell, I hated that term when I first started noticing it being used in movie reviews often. Made me think of Roger and Anita meeting in One Hundred and One Dalmatians... which really is supposed to be a “meet-cute” for Pongo and Perdita I guess, but the marriage of the two humans comes out of it also, and that scene, the crisscrossed leashes and whatnot—that’s got to be the definitive meet-cute. It’s so simplistic, the idea that a unique meeting is the doorway to permanence.

Harry and Sally don’t have a meet-cute per se, either, though. The cute bit when they meet is Harry and his girlfriend at the time, Amanda. That cutesy behavior is the kind of stuff I imagine is in all the romantic comedies I don’t see. Not saying it is, but...

This is weird. I wanted to watch romantic comedies specifically because its not the kind of movie I watch much. In fact, because I’m trying to only use movies I have previously seen for Phase Two of the Groundhog Day Project, my choices were limited. I mean, I could watch something from the 80s, like Pretty Woman but I’d probably just spend the entire week nitpicking all the drastic changes made from the original $3,000 script, a dark drama about prostitution. I think I would have rather seen that movie. Just like I loved Shame but avoid stuff like The Proposal (not to suggest those two movies have anything at all in common).

You’d think a year of a nice feel-good movie like Groundhog Day would make me more open to romantic comedies. The closest to a romantic comedy I made an effort to see in the past year was About Time and that’s a romantic movie, sure, and it’s funny, but it is not a romantic comedy. I think, before I get any further, I should probably define the term. David L. Simpson, Professor at DePaul University, provides this definition:

Romantic Comedy. Perhaps the most popular of all comic forms—both on stage and on screen—is the romantic comedy. In this genre the primary distinguishing feature is a love plot in which two sympathetic and well-matched lovers are united or reconciled. In a typical romantic comedy the two lovers tend to be young, likeable, and apparently meant for each other, yet they are kept apart by some complicating circumstance (e.g., class differences, parental interference; a previous girlfriend or boyfriend) until, surmounting all obstacles, they are finally wed. A wedding-bells, fairy-tale-style happy ending is practically mandatory. Examples: Much Ado about Nothing, Walt Disney’s Cinderella, Guys and Dolls, Sleepless in Seattle.

Love plot: When Harry Met Sally, check. Groundhog Day, check.

Two sympathetic and well-matched lovers: When Harry Met Sally, check. Groundhog Day, check.

United or reconciled: Check and check.

Lovers young and likable: Well, they aren’t the youngest. Meg Ryan is only 27 (or so) during filming, but Billy Crystal was 40. Andie MacDowell was 34, Bill Murray 42. This is no Can’t Buy Me Love, for example, with leads 20 and 16 years old. But, they’re all likable.*

(* minus all of my complaints about Rita being an awful, awful person in Groundhog Day, of course)

Apparently meant for each other... I’ll go with check and check, but I think this might be my biggest peeve with the romantic comedy. I just don’t buy the “meant to.” Even when Harry and Sally are designed to complement one another so well, and they watch movies together by talking on the phone while actually watching them separately in their respective apartments, and know each other’s like and dislikes, I don’t buy it as meant for each other. They are literally made for each other in that they are fictional constructs, but also, taken as real people, I’d call them made for each other, sure, but only because they have spent the time making themselves that way. My personal view on romantic relationships is that they take time. They can start quickly, with a triggering event that gets the ball rolling, but to last they take work, they take time, they take the peeling away of those onion layers.

So, surmounting obstacles: obviously, check and check. But, the obstacles are deliberately contrived. Harry’s theory about men and women—that’s set up right away because that is the crux of the film, proving him wrong for a while until finally proving him right. And thus the ending:

Finally wed: in When Harry Met Sally and Groundhog Day there is no literal wedding between the leads, but we assume permanence. Plus both films do involve weddings (Groundhog Day‘s no longer onscreen like it was in Rubin’s original script). Day 288 - fix your bra, honey, I suggested that references to marriage represented “a reification of traditional gender normative roles.” Marie and Jess serve as a deliberate counterpoint to Harry and Sally. Their relationship turns romantic right away...

...you know, like it’s supposed to be.

Comments

Post a Comment