inside the men, there were three bullets

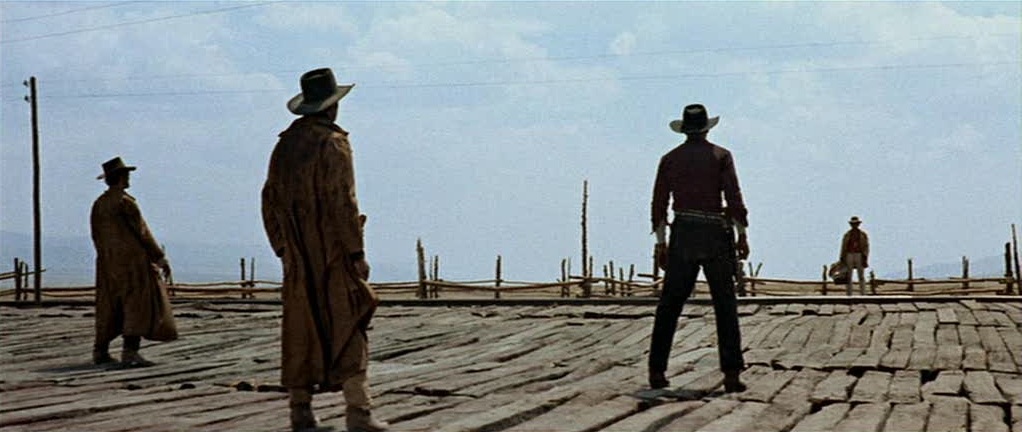

That painting by Frank McCarthy, which hangs at the Autry Western Heritage Museum near here, was used in some of the posters for Once Upon a Time in the West.

And, I'm a good half hour into the movie before I type anything tonight. I'm just enjoying watching the ways Leone puts stuff together. He's obviously influenced by Ford, but he showed his tics with the Dollars Trilogy--the extreme closeups, the long shots. Here he makes generous use of slow pans as well, a lot more camera movement than with the Dollars Trilogy. Plus, he did some filming (at least a few establishing shots) in Ford's stomping ground of Monument Valley, not just Almeria, Spain.

I can't find the original article, but I read a bit about how Leone considered his Westerns, especially The Good, the Bad and the Ugly, to be satire of the American Western. In pacing alone, that film and this one definitely deconstruct the action down the minutiae, offering us mysterious strangers--the Man with No Name or, here, Harmonica--who come into town and rather than save the place, are not up to so much good. Eastwood's Man with No Name is fairly amoral and so seems Charles Bronson' Harmonica, but Henry Fonda's Frank seems more blatantly evil... well, inasmuch as Leone is probably trying to suggest that evil men exist. He is the the Bad of this film.

Once Upon a Time in the West includes scenes that echo specific earlier scenes in other, American Westerns. I could list them off, but others have already made the lists--for example, these Notes of a Film Fanatic. The point is not to catalog the references but to recognize the reason for them. Like Tarantino or Rodriguez aping Leone years later, or Leone occasionally aping Ford (though usually playing things quite deliberately differently), the point is that filmmakers echo one another not just because it makes for good cinema, taking something that worked before and using it again--I mean, that's how we get genre--but also because film is like a language. Sometimes, its use is rudimentary, sometimes its use is poetic, beautiful. Film, like any art, builds on itself, echoes lines of visual poetry to evoke old themes, to invoke the myths we've built around them. Leone was actively working to deconstruct the Western genre, the myth of the American Old West as put to film. Leone, an Italian filming primarily in Spain, is playing with American myth.

(For the record, I've got no problem with that at least on the surface. Plenty of American-made films play in the sandbox of other national and cultural myths... Take Clash of the Titans for example... well, that's British- and American-made, I think, but not Greek-made. What matters is a) is the film good? and b) does it pay respect to the original culture's ideas? And, as a lover of film before I was ever a lover of history, I tend to value a over b. Not that I won't critique a film for failing at b.)

That Film Fanatic piece linked above tells the story of how Leone didn't want to make another Western after The Good, the Bad and the Ugly but the studio demanded it, and he assented as long as he got to make the film he wanted to make. He worked with Bernardo Bertolucci and Dario Argento to put together the concept for this film... his purpose was "to use some of the conventions, settings, and stereotypical characters of the American Western, and a series of references to individual Westerns--but to use these things to tell my version of the story of a birth of a nation." It is important that Once Upon a Time in the West involves the railroad. But, not only that--a railroad tycoon who is dying from tuberculosis.

(This scene right now, in which Harmonica holds Jill (Claudia Cardinale) down and rips her dress--played seriously, and almost brutally, paints a far more violent picture than some of the Western heroes we've seen so far, who might win over a woman by doing just this. Lewt in Duel in the Sun being the obvious exception. It turns out, of course, Harmonica was just making her look vulnerable for the men who were coming. The movies plays with our expectations.)

Gabriele Ferzetti's tycoon, Morton, got on his train at the Atlantic and doesn't want to get off of it until he can see the Pacific outside his window. But, he may not make it. He's already only able to walk with the use of crutches or specially built handles that hang down in his fancy train car. When the mysterious stranger makes a habit of playing a harmonica and the big bad railroad tycoon who just had a family murdered can barely breathe, we have a clear exemplar of Wright's (1975) strong/weak binary opposition. Harmonica is strong, Morton is weak. But Frank, who works for Morton, is also strong, but he's a different kind of strong, more intent on showing off his strength than Harmonica is. Harmonica is willing to just stand around and creep people out by playing his Harmonica in the dark. On the one hand, Leone is playing with the normal conventions of the classical plot. But he's also taking it a little further by making the villain more than just weak. The capitalist, the guy who is helping form the nation from coast to coast--he's unable to even stand on his own. Brett McBain ordered lumber to build a station and a town, knowing the train was coming. But he was murdered by Frank.

And with whom does Jill go to bed? Not Harmonica, which would have made sense in the classic Western, and even Leone's previous films. Frank, the man who murdered her husband and three kids that should have been hers. Now, maybe she didn't care about the kids, maybe she barely even cared about the husband, maybe she was in it for the money--this guy could afford to build a town on his property. Or, maybe she is faking it because she knows Frank might kill her as well. But, the scene doesn't play that way. It plays like the love affairs we've seen implied in previous American Westerns. Someone wrote in the wikipedia page on the film to say that Frank rapes Jill, but the movie never suggests this. The film never even suggests that she doesn't want to be there. We can infer it, but the film does not imply it. With as little setup to that scene as the film offers, we might as well just assume that Jill is being opportunistic because she thinks Frank is going to come out on top.

That this isn't clear seems deliberate. Again, Leone playing with the conventions of the genre. In his version of the Western, oddly enough, there is no obvious good, nor clearcut bad. American Westerns, with the likes of the violence-prone Earps in Gunfight at the O.K. Corral or the gunfighter--played by Henry Fonda no less--in Warlock--had been leaning this way, but Leone takes it further than they had at this point. Ethan Edwards in The Searchers, for comparison, is a man used to violence but he doesn't revel in it like Eastwood's Man with No Name or Bronson's Harmonica. American Westerns, prior to this, liked to paint a picture of men who turned to violence out of duty. These men turn to violence because a) they don't have anything else and maybe even b) they enjoy it.

Comments

Post a Comment