they were decently treated, they were decently fed and then they were decently shot

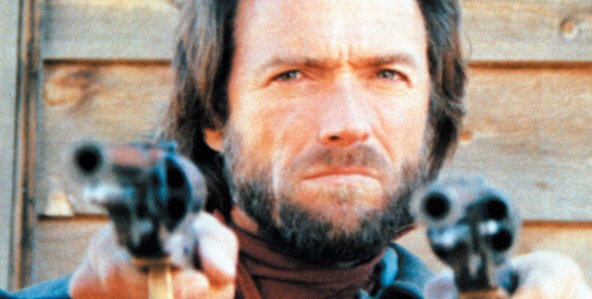

Clint Eastwood once again (directing as well as starring)--The Outlaw Josey Wales.

By the time the opening credits come to Eastwood's director credit, we've seen the titular Josey's wife and son murdered by Union soldiers and Josey join up with Confederate guerrillas. We've seen more war footage already than in the entire Civil War section of How the West Was Won, and just barely over ten minutes in, the guerrillas are surrendering. But, not Josey. He stays right where he is and says, "This isn't what happened last week! Have you all got amnesia? They just cheated us! This isn't fair! He didn't get out of the cock-a-doodie car!" Sorry, wrong film. More like, they just cheated us, we lost the war and have to be one country again.

The cheating follows, actually--the massacre of the surrendered guerrillas...

And, the Western hinges on the Civil War once again. And, it's a sore subject in this country in the present. As Josey tells Lone Watie (Chief Dan George), "You know there ain't no forgettin'." Debate about the Confederate flag and its public display after a shooting last week, in case you're reading this some time in the future. It's not just this one genre of film that keeps returning and returning to the Civil War. Race relations, North/South relations, Republican/Democrat relations--this keeps coming back to the Civil War, a nation divided... Last week on The Daily Show with Jon Stewart, Stewart had a powerful line--

I honestly have nothing other than just sadness once again that we have to peer into the abyss of the depraved violence that we do to each other and the nexus of a gaping racial wound that will not heal yet we pretend doesn't exist.

The bigger problem is that there's more to it than race. The South was built up on pride and aristocracy, the plantation-dwelling elite living off the labor of their slaves and not wanting to be told what to do by politicians off in Washington. Josey's rage here begins with the murder of his wife and son but it plays as a sort of metaphor for the entire war, the entire South's anger and frustration over losing their way of life. However reprehensible their way of life may have been, built as it was on slavery, it was still their way of life and the Union destroyed that way of life. Destroyed their economy. Destroyed their identity. Of course there was rage. I'm reminded of a line from John Wilkes Booth in the stage musical Assassins--"What I did was kill the man who killed my country." Whether that country was the Confederacy or the United States of America, it had been torn apart and would need rebuilding. Forcing secessionists back into the fold may result in a singular nation again, but it will also keep all the hurt feelings around. The wound will remain to fester--as with the emergence of the Ku Klux Klan and its sequels decades later and decades later again. The ghosts of the rebellion would be passed on to generation to generation and this country would remain a nation split in half, held together by the sheer will of the federal government, much to the chagrin of a good portion of its people. And, there would always be those who don't want to bow to power.

And, there are those who hold onto outdated values that have no place outside the plantation... but the race issue--that's not related to this film.

(Even though, the novel on which it is based was written by a guy who was in the Klan. And, who (probably) wrote George Wallace's infamous "segregation forever" speech. "Let us rise to the call of freedom-loving blood that is in us, and send our answer to the tyranny that clanks its chains upon the South." A line from Wallace's speech that could easily have come from the likes of William T. "Bloody Bill" Anderson (John Russell) as he led his Confederate guerrillas.)

But war--a nation torn apart--that falls right into this film's wheelhouse. In an interview with the Wall Street Journal in 2011, Eastwood says (specifically regarding his film J..Edgar, but it easily segues into talk of Josey Wales),

Society is at odds with itself... They want law and order but... I was always intrigued by this guy [J. Edgar Hoover] who was frustrated by not being able to solve problems due to the obstacles put up by society itself--by the bureaucracy in society...

The law cannot always do its job, certainly. But, the law can also go too far. Here, for example, Josey is only an "outlaw" because he didn't surrender. Sure, yeah, he then killed the men doing the massacre that followed, but can you fault him for that? Similarly, once he has been branded an outlaw, can he be faulted for defensive kills that follow? Back a man into a corner and he will fight back.

Eastwood calls this film an anti-war film. "I saw the parallels to the modern day at the time," he says. "Everybody gets tired of it, but it never ends. A war is a horrible thing, but it's also a unifier of countries." Regardless of where those in the Confederate States stood when the Civil War began, for example, four years of war would pull them together, I would think. After Sherman's March, for instance, I would imagine a very unified South, hurt and angry and bent on a revenge it barely had the manpower to enact anymore.

That Josey keeps having to defend himself (and barely seems the offender) suggests an interesting angle, especially since he was with the Confederacy. Or maybe it's just the usual romanticization of the outlaw, regardless of how or why he became an outlaw. But, then Josey collects his company, and one sees the kind or brotherhood you might see within the war. In that Wall Street Journal article, Eastwood references "the urgency and the camaraderie, and the unifying" in war. "But," he says, "that's a sad statement on mankind, if that's what it takes." Josey joined up with those guerrillas out of anger and rage. He's building his company now--Lone Watie and Little Moonlight (Geraldine Kearns) so far--out of something a little better, the need for brotherhood and support, and help with survival itself. It seems more noble.

The outlaw is more noble than the soldier. He tells Ten Bears (Will Sampson), "I'm saying that men can live together without butchering one another."

It does seem a real shame that it takes violence and adversity to draw people together. I often think of this in the context of the nation-- every form of colective identity, but especially the nation. I wish nationalism could define itself in terms of peace rather than always in terms of war. I also think of it in the context of that scene in Casablanca where everyone sings the Marseilles. Why does that solidarity have to disappear when the fight is over? It's a real shame.

ReplyDelete