jason voorhees is dead

Today was not as long as yesterday. Haven't watched today's movie yet, either. It's Friday the 13th: A New Beginning.

(By the way, the stuff I would have included had I not become eminently susceptible to attack from Freddy Krueger (assuming I was in Springwood, Ohio, not Lake Oswego, Oregon)--I will throw some of that into this blog tomorrow, when I watch A Nightmare on Elm Street 2: Freddy's Revenge.I kinda wish I'd at least had a dream about Freddy Krueger since I was starting to fall asleep before the movie ended last night. But no, instead I manage a couple sentences with a couple typos, a sad little excuse for a blog entry.)

I wanted to talk about genre since, with A Nightmare on Elm Street last night, I got into the second third of this "month" of slasher films. Nowell (2011) provides an elaborate description of what makes a slasher film a slasher film. First, I rather like Nowell's definition for what genre is:

At its core, film genre is a system of communication comprising two components, the label and the corpus. A name is assigned to a number of films because they are considered to share similarities that distinguish them from other films, this bringing order to relative chaos. (p. 15)

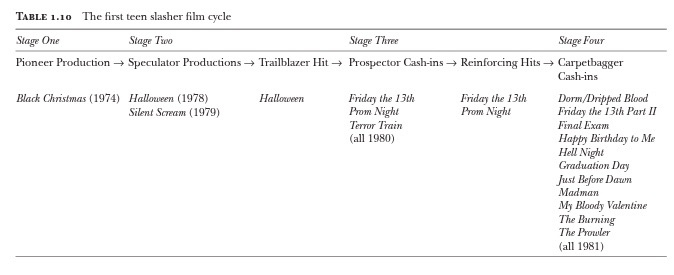

So, basically, genre is how we label films (in this case) based on similarities, and also the substance that makes up that genre, i.e. the films contained therein. The relationship between the label and the corpus, of course, is somewhat fluid. One film that might be a slasher film, for example, may contain just enough differing details to serve as the start for defining a separate subgenre. At first, it would be considered a slasher film, but then another film would come along and reinforce the new subgenre. Take a look at this table from Nowell's book (p. 55):

That's how Nowell depicts the birth of the slasher film as a subgenre. When Halloween came out in 1978, it was not yet a slasher film. That label didn't really exist. Genre is defined in retrospect. Nowell, in defining the slasher film, writes:

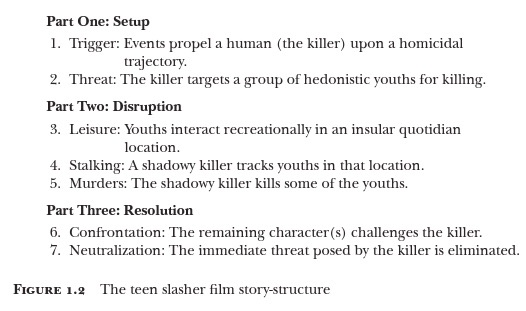

The teen slasher story-structure depicts a shadowy blade-wielding killer responding to an event by stalking and murdering the members of a youth group before the threat s/he poses is neutralized.... This sequence of events comprises three parts: the setup, featuring story-point one (trigger) and story-point two (threat); the disruption, featuring story-point three (leisure), story-point four (stalking), and story-point five (murders); and the resolution, featuring story-point six (confrontation) and story-point seven (neutralization). The setup explains why the killer is targeting the youth group. The disruption oscillates between the youth group members' recreational interaction, and the killer stalking and murdering them. During the resolution, the killer is confronted by the surviving character(s) and the threat that s/he poses is extinguished. (p. 20)

Simplified (p. 21):

Let's look at Friday the 13th--the first one, though arguably each sequel is simply a reset back into the midst of the story-points that Nowell details. The trigger we only hear about (though we will see it in flashback later); Pamela Voorhees (though we don't know who she is yet) is responding to her son's death because she blames the counselors. The threat is established when Mrs. Voorhees kills two counselors. Then, we jump forward in time to the leisure. In this case, it's a handful of camp counselors who can barely be bothered to do the work of readying the summer camp for its campers because they are too busy playing. The stalking continues along the way, getting murders in just often enough to maintain the threat. Then, we get to the real series of murders that forms the buildup to the climax of the film. That climax is Nowell's confrontation, which includes all of Alice's interactions with Mrs. Voorhees. I say all of the interactions because Friday the 13th plays as a whodunit as much as a horror film. So, the revelation of Mrs. Voorhees' identity and motivation is just as important in constructing the climax of the film as the violence that ensues between her and Alice. And, that violence ends in the neutralization.

It is worth noting--and Nowell doesn't mention it (here, at least)--that the neutralization is effectively reversed once the sequel comes along. Well, not in the case of the transition from Friday the 13th to Friday the 13th Part 2, since Jason replaces his mother as killer, but with additional sequels. The Final Chapter doesn't explain how Jason manages to get up again at the beginning of the film, A New Beginning doesn't actually involve Jason, but then Tommy Jarvis' actions at the start of Jason Lives, meant to ensure Jason cannot return again, ironically result in bringing Jason back--a bolt of lighting to the chest wakes Jason like Frankenstein's monster. In The New Blood, Tina's guilt over her father's death causes her to inadvertently use her mental powers to release Jason from his watery grave. And, in Jason Takes Manhattan, it is again electricity that brings Jason back, not lightning but a broken powerline. By the time they get to Jason Goes to Hell, though, explanation is left behind again. It doesn't matter that the neutralization is reversed--by this time, that is a given--Jason is simply back, again. By reversing the neutralization, each sequel effectively becomes a part of the previous story, replacing it's final story-point with repetition of the earlier story-points.

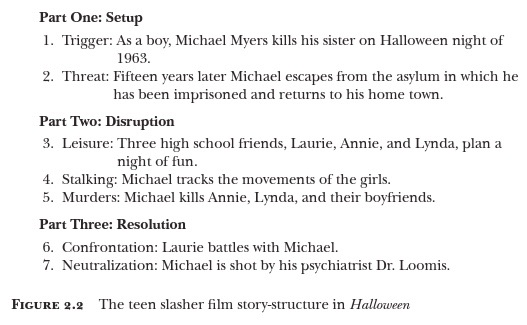

Another breakdown, this one from Nowell (p. 82):

Michael's neutralization is reversed within seconds of happening, of course, so the film can leave us with a sort of cliffhanger ending. Beyond the requisite immortality of Jason and Michael and Freddy from film to film (Note, at this point in my "month" of slasher films, Leatherface has yet to be dispatched at the end of a film. The original The Texas Chain Saw Massacre leaves him alive and well as Sally gets away.) are other continuing details. Nowell explains some more about the slasher film:

Bound to the teen slasher story-structure are three iconographic elements: a distinct setting...

For the Halloween series, Haddonfield, Illinois, and more specifically the Myers house. For the Friday the 13th series, Crystal Lake, New Jersey and the various campgrounds and residential properties around the lake. For the Nightmare on Elm Street films, Springwood, Ohio.

...a shadowy killer...

Michael Myers, Jason Voorhees, Freddy Krueger, Leatherface, etcetera.

...and a group of youths. Action is confined largely to a single non-urban location which, as a result of being labyrinthine, remote, and sparsely populated, transforms the everyday sites of the American middle-class into ideal arenas for activities that otherwise would be restricted, enabling youths to pursue and realize their hedonistic urges and, as Martin Rubin [1999] notes, permitting a lone blade-wielding stalker to pose a grave and unnoticed threat to a collective of physically fit young people. (p. 20-21)

On those youths, Nowell expands a bit; he writes:

The inclusion of sketched character-types in the group minimizes characterization to prevent audiences from becoming saddened or shocked by their deaths. (p. 21)

Simple characters exist for a deliberate reason--to let us be ok with them dying. The camera puts us in the position of the killer and the script provides victims that may amuse us but that we just won't care about. In the average slasher film, you can bet that any real character depth will happen only with characters that will survive. There are exceptions, of course, just as with any rule.

On the shadowy killers, Nowell expands as well; he writes:

Whereas stalking undermines potential sympathy for the killer by demonstrating that his/her actions are premeditated, depicting a killer as "depersonalized, devoid of psychological detail, and faceless" (Rubin, 1999, p. 163), enables filmmakers to sidestep suggestions that s/he acts sadistically by mobilizing a human monster that, while uncompromising and merciless, behaved like a focused and efficient assassin." (p. 21)

The killer walks the line between unforgivable brutality and faceless murder we can get behind and even cheer. A good example of an exception to this would be in Rob Zombie's Halloween 2 (which I will not be watching for this blog). Michael Myers is so deliberate and brutal in his killings in that film that it is much harder to cheer him on. On the other hand, picture the murder of Kelly Meeker in Halloween 4: The Return of Michael Myers. We in the audience are inherently sexist, so we probably dislike her just a little more than we dislike Brady for having cheated on Rachel with Kelly. Either way, both of them die. My point is, when she dies, maybe we cheer a little more because her simplistic role has been a sexed up girl intent on stealing one of our leads' boyfriends. When Michael goes after her, we're okay with it. The conservative mentality of the slasher film rears its head.

Something Nowell doesn't detail in the above sections--something that is a major element of Clover's (1988, 1992) take on the slasher film--is the use of the first-person POV camera putting the audience in the role of the killer. That detail--which allows us to experience murders as if we are committing them--is vital to an understanding of the slasher film. Each new group of young people in each new sequel is not simply a new group of victims for our shadowy killers but, more importantly, a new group of victims for us. Our ticket purchases kill these people.

Works CitedNowell, R. (2011). Blood Money: A History of the First Teen Slasher Film Cycle. New York: Continuum.

One of the biggest complaints about FT13th Part 5 is the payoff to the identity of fake Jason. Basically it's a character with barely a minute worth of screen time at the start of the film and who's triggering moment that makes him turn murderer is one of those completely out of the blue revelations that even the characters at the end, when he's unmasked post death, go "WTF?".

ReplyDeletePart 5, that said, is still a decent film in spite of the bait and switch junk. And it laid the groundwork for how Crystal Lake would be portrayed in later films, as far as recasting it as a faux Southern Gothic sleazepit.

I think structurally, the identity payoff in A New Beginning is not much worse than in the original. What makes the original work better, though, is perhaps that Mrs. Voorhees gets screentime after we know she's been killing people. She's more of an actual character, even if she enters into the story quite late. The father in A New Beginning just seems so insignificant that it's hard to care.

Delete