there's roadkill all over texas

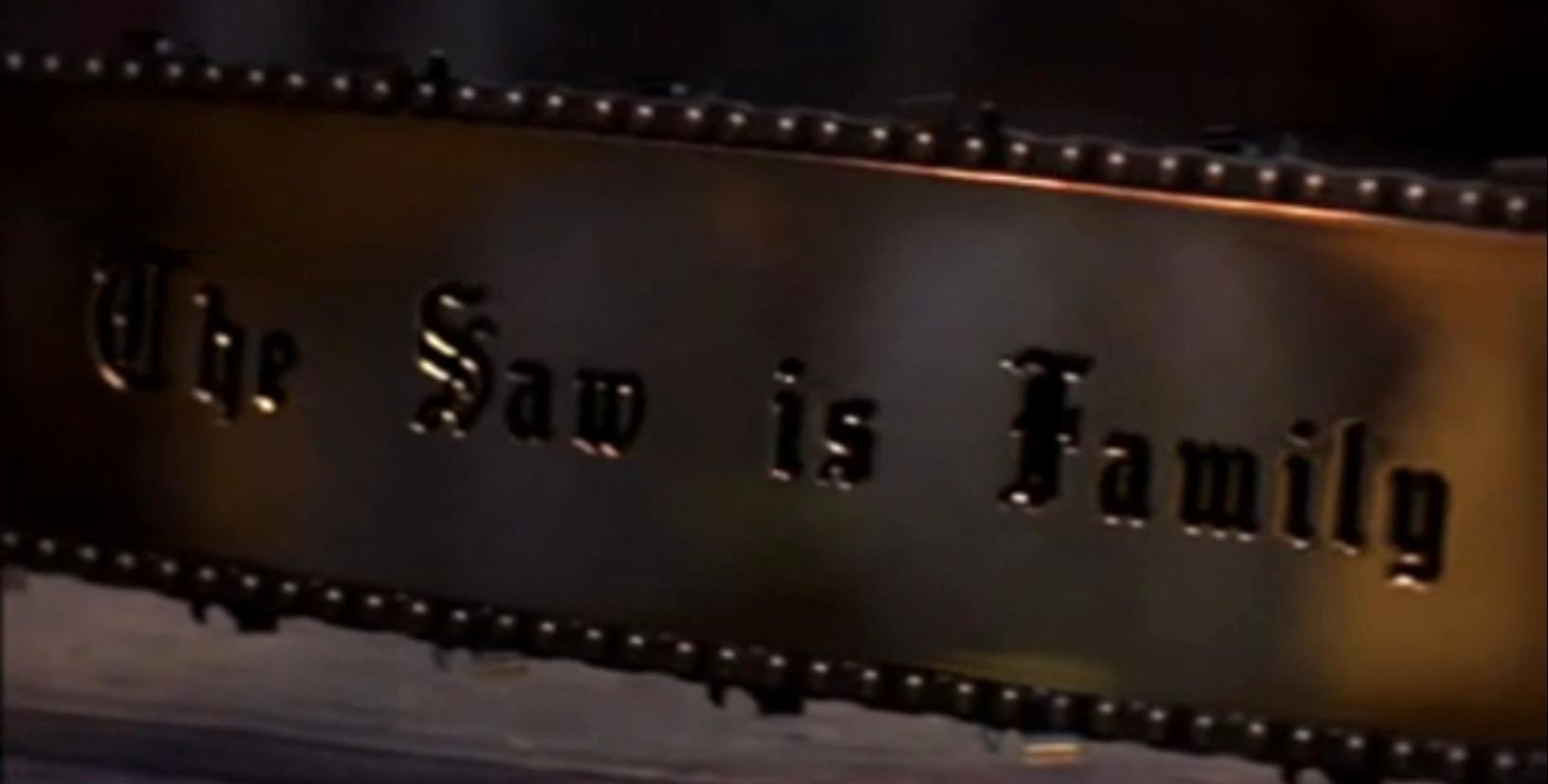

The opening text crawl for Leatherface: Texas Chainsaw Massacre III insists on the verisimilitude of this being based on real events. The fact that Norman Bates in Psycho was based on the same guy that inspired Leatherface ought to tell you how real this story is.

I’ve only seen this movie once before, I’m pretty sure.

I don’t actually remember if Viggo Mortensen’s character is part of the Sawyer clan, but I figure if Strider offers you directions someplace, you should listen.

It really only occurred to me now, with only two potential victims present in this film, that Texas Chainsaw Massacre 2 was not really a slasher film. There just weren’t enough victims.

(And, from what I remember of chainsaws—a family friend from when I was a kid was pretty much a lumberjack, so he has a few—you start them like you do a lawn mower, a little pull cord, and the engine gets going. The noise that you hear when Leatherface comes at Michelle and Ryan when they’re changing the tire is the noise from actually starting the blade moving. But, the engine should have already been running, thus making more noise than his creaky knee brace.)

And, a third victim—Benny—is introduced. Still, this is more in the genre of The Hills Have Eyes or Wrong Turn than a Slasher Film.

Rieser (2001) takes issue with Clover’s (1992) analysis of the male audience-Final Girl relationship; Rieser argues, “the male spectator does neither straightforwardly nor entirely positively identify with the female victim-hero and thus does not necessarily embrace an antipatriarchal and/or passive position” (384).

And, just as I was getting into Rieser because Benny (male) is the proactive one here, fighting back against Leatherface, another girl is introduced. She seems a bit out of it... and she’s killed a few minutes later—did she even have a name?

Anyway, Rieser makes a distinction between the male audience member identifying with the Final Girl—which he says doesn’t happen—and that male audience member empathizing with her instead. “Witness, for example,” Rieser writes,

that the gaze of the camera is only sometimes with her (and even more rarely through her eyes), while at other times “her” point of view is subverted by shots that are looking down at her, huddled and shivering in a corner... Thus, the film lets a male spectator feel her terror, but it remains nonetheless a female who serves as the site/sight of terror. (384-385)

Creepy little girl added to the family, and sure enough Strider is one of them, too.

Personally, I’d side with Clover on this one. Using little more than my own experience, of course, I would argue that the male audience member does, indeed, identify with the Final Girl, because in my experience a good audience member—and I don’t mean to make a True Scotsman argument here—identifies on some level with any character, but especially with lead characters. And, in the slasher film, though I have previously pointed out that it may be contradictory, we can identify with both the killer and the killed, the masked killer and his Final Girl. Rieser may have a point, though, when he argues that the Final Girl might be “less... a stand-in for the male viewer than an imaginary potential partner (‘my girl’)” (385). It certainly helps—in the common parlance of Hollywood films—that the Final Girl is attractive, that her stalker is masked and/or deformed. It makes connecting with her easier. Additionally, siding again with Clover, the male audience member can identify with the killer specifically because he is masked and/or deformed; he serves as our id, wanting the Final Girl perhaps sexually as much as the killer does. And, neither the killer nor we in the audience can have her, not just because she is virginal and unavailable in the context of the story—

(Here, again, is a way this film is not a slasher film—there is nothing particularly virginal about Michelle. Though she did back down from bashing in that armadillo’s head early in the film, remember how quickly she was to head for a rock to kill it in the first place. Her reluctance doesn’t make her necessarily more feminine but simply more human.)

—but because in being on the other side of the screen, being fictional, she is literally unavailable. The killer—with his Cloverian psychosexual fury, acts out in violence to go after first everyone around her, then after her. We males in the audience (and the females, too) may cheer as the killer goes after her, but realizing our culpability in the action before us, and, yes, identifying with her finally, we switch sides, cheering her on as she is victorious over the killer.

Rieser continues:

...the Final Girl does not so much embody what a male adolescent would want to be himself but how he would like his girl to be; not passive but not too active

—Michelle only survived to fight back herself just now because Benny showed up with a gun—

and above all, turning down (indeed against) that other man who desires her, while at the same time fighting her way out of a somewhat too restrictive (read: parental) definition of girlhood (now we don’t want her too chaste, do we?). (385)

Rieser argues, appropriately given what he’s said so far, that this approach is “entirely in accordance with patriarchal power relations. Indeed it corresponds perfectly to the established masculinist practice of ‘protecting’ women in the male’s sphere of influence (wife, girlfriend, sister, daughter) from other men” (ibid). This viewpoint, while consistent, fails at this point, I would argue, because it is the Final Girl who commits the last act of violence. It is not her protector (usually)—Tommy Jarvis in the Friday the 13th series violates the Final Girl standard quite deliberately—who is active in the end; hell, in the original Texas Chain Saw Massacre and in this one, the girl’s initial protector—for Sally Hardesty both her boyfriend and her brother (even if he is in a wheelchair), for Michelle, Ryan—is long dead by the end of the film. Sure Benny keeps showing up to help Michelle out, and sure Dr. Loomis keeps saving first Laurie Strode and then her daughter Jamie. And, the Final Girl in Friday the 13th Part 2, The Final Chapter, A New Beginning, Jason Lives, The New Blood, and Jason Takes Manhattan makes it out alive alongside a Final Boy.

(Final note: Kane Hodder as stunt coordinator. Jason and Leatherface together, even if indirectly. They would meet in comic books, but I’ve never read any of those.)Works Cited

Clover, C.J. (1992). Men, Women, and Chain Saws: Gender in the Modern Horror Film. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.Rieser, K. (2001). Masculinity and Monstrosity: Characterization and Identification in the Slasher Film. Men and Masculinities 3:4. 370-392.

Comments

Post a Comment