join us in the definitive nightmare

Note #1 - I skipped a movie on my list today—I will get to it in a few days—because I wanted Day 450 of this blog to be something I knew I liked. I barely remember Texas Chainsaw Massacre: The Next Generation but I know it had some issues with its release... and I’m using that to move it down the line for this “month” of slasher films. In case you haven’t been paying too much attention, I’ve been going in order of cinematic release (in the US). I skipped that particular film past its initial release to its later release, so that I could watch...

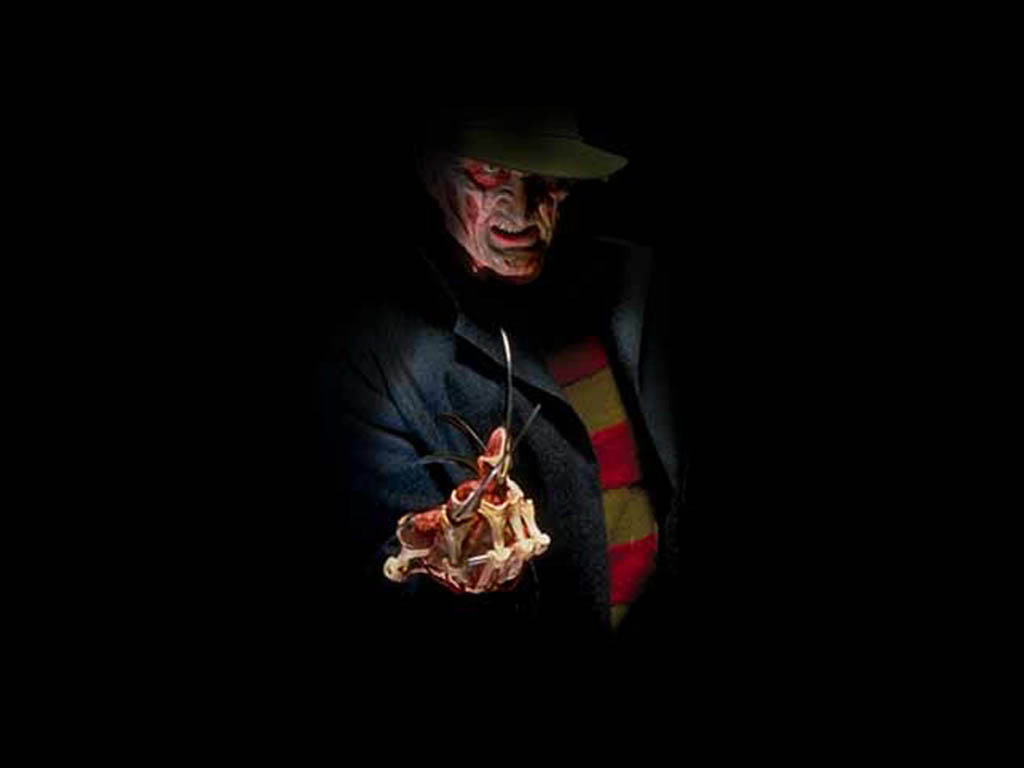

Note #2 - Well, so that I could watch Wes Craven’s New Nightmare tonight. And speaking of release dates, I first saw this film before it was released in theaters, saw it at a test screening at the United Artists Marketplace Theater in Old Town Pasadena. At the time, it seemed like New Nightmare was just a working title. But, the prospect of Wes Craven returning to the series was good reason to go see the film as soon as possible.

Now, onto the movie.

Starts with a dream that is about making a movie, already getting into the metafictional side of things. Then, the earthquake, which is an interesting detail because the 1994 Northridge quake happened during the filming of this movie. According to Peitzman (2014), they already had an earthquake written into the story and, “suddenly, production had access to real-life disaster footage they could incorporate into the final cut... The eerily timed disaster was particularly strange on a film that details breaking the fourth wall. In this case, it was almost as though the earthquake had rumbled through it.”

The bit with Dylan watching the original A Nightmare on Elm Street but only screaming when Heather turns it off amused me at the time, but just recently I heard, or read, that kids are actually more likely to be frightened by horror films when their parents are present... something to do with younger kids just not always comprehending exactly what to be afraid of, so they take cues from their parents, and if their parents are frightened, or even a little tense, the kid is more likely to be as frightened, as tense, or more so.

Ebert (1994), writes of the metafictional nature of New Nightmare in his review:

That’s part of the fascination, as “Wes Craven’s New Nightmare” dances back and forth across the line separating fantasy from reality. This is the first horror movie that is actually about the question: “Don’t you people ever think about the effect your movies have on the people who watch them?”

Heather Langenkamp, quoted in Peitzman, says, “It’s not like we’re looking at the audience and winking at them. We’re taking the audience into a new spatial relationship with the real lives of people who act in them.” Peitzman continues:

Breaking the fourth wall... is an inherently distressing concept—it disrupts the sacred relationship between the audience and the movie—but breaking the fourth wall in horror in horror is downright terrifying.Because in horror, when you knock down that wall, you might not like what you find on the other side.

Movies that break that fourth wall and do it well—I love those movies. And, it should be clear that I love horror films by now, so New Nightmare is a great film for me. It contains some interesting ideas about the link between fiction and reality, why we choose to watch (or read) what we choose to watch (or read), why we choose to participate in the stories that we participate in. It also contains some very bleak notions about the ways we might deal with grief—Dylan climbing on top of the playground rocket and saying afterward, “God wouldn’t take me”—and about what horrors we (need to) create to deal with the world around us, not to mention a little bit of religion (or at least creation)—“Freddy” tells Heather/Nancy, “Meet your maker,” except having become Nancy at this point in the film, she has literally already met her “maker;” she has known him for a decade. The fictional versions of Heather Langenkamp, Robert Englund and Wes Craven have certain demons they need to exorcise. Together they made the original A Nightmare on Elm Street and they need to answer for that. In Peitzman, Craven talks about why we watch horror films:

You don’t enter the theater and pay your money to be afraid. You enter the theater and pay your money to have the fears that are already in you when you go into a theater dealt with and put into a narrative... Stories and narratives are one of the most powerful things in humanity. They’re devices for dealing with the chaotic danger of existence.

I’m reminded of Benesh (2011)—

(Benesh’s dissertation is a source I never thought would come up after the year of Groundhog Day was over, but sometimes the unexpected happens.)

—and her take on how film becomes personal. She writes:

Thus, for viewers, no less than for Phil [or Heather], an imprint remains as during the film he audience members “introject” or take in its psychic content including symbols, images—

Like Dylan in New Nightmare incorporates the fictional Freddy into his dreams, we incorporate the fictional Freddy into, well, our ideas of what horror is. Not just horror in film, but horror inside us, around us, horror within the entire world, the same idea that Craven was getting at above.

—and narrative, as well as projecting individual personal concerns. After the film, if it is particularly “resonant,” the process continues as the film “plays on” in the viewer’s mind. A personal “edition” of the film is thus created and is assimilated into the psyche of the viewer. (p. 8)

This film asks—and the nurse does so quite explicitly—what happens to us when we watch horror films, what happened to our children when we let them watch horror films. Benesh (by way of Izod (2000)) links our viewing of film to dreams. This film invites us to make that connection quite explicitly. Dreams and film, film and reality—the lines are blurred by the story in New Nightmare.

And, keep in mind the story that inspired Craven’s original film. “I’d read an article in the L.A. Times,” he tells Vulture Magazine,

about a family who had escaped the Killing Fields in Cambodia and managed to get to the U.S. Things were fine, and then suddenly the young son was having very disturbing nightmares. He told his parents he was afraid that if he slept, the thing chasing him would get him, so he tried to stay awake for days at a time. When he finally fell asleep, his parents thought this crisis was over. Then they heard screams in the middle of the night. By the time they got to him, he was dead. He died in the middle of a nightmare.

Dreams have power over our thoughts and our behavior. So do films. I think it has been proven that just watching horror films, for example, doesn’t turn one homicidal, but it is difficult to imagine that there is not some correlation between the choice to watch darker films and having darker thoughts, something like the Mean World Syndrome—are horror fans perhaps more paranoid about strangers? Do they assume the worst about people they don’t know? Are they afraid of the dark because there are real dangers lurking in it, or because their mind is full of dangers real and imagined that are just a little more visible in the dark than in the light of day?

I wouldn’t suggest a definitive answer to any of these questions. These are more things to think about than things to really know.

Something perhaps more interesting in the end of this particular film, since I keep coming back to Clover (1992) in this “month” of slasher films: Heather/Nancy stabs “Freddy.” Unlike the “feminist Final Girl” she was in the original A Nightmare on Elm Street according to Christensen (2011), Nancy here takes up the phallic weapon and attacks. Of course, she does so out of motherly protection, so take Clover’s notions with a grain of salt. It is interesting to note Lankenkamp’s reaction to Freddy’s attack at the end of the film:

When he finally turns into a snake at the end and he’s wrapping himself around my throat and strangling me that way, it’s the only scene that I’ve ever had nightmares about, because it really, to me, was Freddy... He humiliated me in a way. It was really scary. It was really mean-spirited. It was a very sexual power that he was expressing. There was nothing funny about it. ( Peitzman )

He was no snake, though. Instead, it was his tongue, stretched out in what could easily have been a comic moment in one of the earlier sequels but which here does come across as real power Freddy is exhibiting over Heather/Nancy. And, yes, the tongue is very sexual. And, this sexual attack is thwarted when Dylan stabs Freddy’s tongue. And, soon thereafter, Freddy loses his power and dies.

In the end, the film ends just where it began as Nancy reads the script to Dylan. I’ve got another week almost of slasher films, but really this one right here would have made a great ending to this “month.” While some slasher films stretch the definition of what a slasher is, in certain ways, they are all very much the same, and taken together they become quite repetitive, and to end back at the beginning is thematically appropriate.

Works CitedBenesh, J.E. (2011). Becoming Punxsutawney Phil: Symbols and Metaphors of Transformation in Groundhog Day (Doctoral dissertation). Retrieved from ProQuest Dissertations and Theses. (Accession Order No. 3450252)Christensen, K. (2011). The Final Girl versus Wes Craven’s A Nightmare on Elm Street: Proposing a Stronger Model of Feminism in Slasher Horror Cinema. Studies in Popular Culture 34:1. pp. 23-47.

Clover, C.J. (1992). Men, Women, and Chains Saws: Gender in the Modern Horror Film. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Ebert, R. (1994, October 14). Wes Craven’s New Nightmare [Review]. http://www.rogerebert.com/reviews/wes-cravens-new-nightmare-1994

Peitzman, L. (2014, October 15). How “New Nightmare” Changed the Horror Game. BuzzFeed. http://www.buzzfeed.com/louispeitzman/how-new-nightmare-changed-the-horror-game

Marks, C. & Tannenbaum, R. (2014, October 20). Freddy Lives: An Oral History of A Nightmare on Elm Street. Vulture. http://www.vulture.com/2014/10/nightmare-on-elm-street-oral-history.html

Comments

Post a Comment