this town loves prime meat

The original The Texas Chain Saw Massacre was released 1 October 1974, but the crawl at the beginning of The Texas Chainsaw Massacre 2 establishes that it happened on 18 August 1973. This one was released 22 August 1986, but is set “14 years” after the original. That isn’t important information, but after yesterday‘s blog entry, the discrepancy was noticeable for me.

What is important to note is that this film doesn’t really seem to be cashing in on the popularity of slasher films. It’s not one of Nowell’s (2011) “carpetbagger cash-ins.” Hell, I’m not sure this film falls within Nowell’s “first teen slasher film cycle” in terms of timing. Looking at the release dates of just the more popular slasher films I’ll be watching this month, I see no real gap from Halloween in ’78 to Halloween H20: 20 Years Later in ’98. That is to say, there’s a 4 year gap between The Texas Chain Saw Massacre in ’74 and the original Halloween, and a gap of four years after H20 to Jason X. I think Nowell’s cycle might be rather arbitrary.

A couple content notes:

1) A reference to Rambo III, which wouldn’t actually exist for another couple years, and the metal plate guy—called Chop Top, apparently—mentions having a ‘Nam flashback maybe a minute later, says his accidental injury by Leatherface is “gonna send me back to the VA hospital.” I have previously linked the emergence of the slasher film to the sexual revolution of the 1960s—the punishment of moral depravity and hedonism after mainstream folks had been so afraid of hippies being a somewhat reasonable cinematic response to the counterculture and everything that came along with sexual and political revolution. I don’t think I ever specifically linked the violence of the 60s, and especially of the Vietnam War to the violence on display in the slasher film. Considering my review of A Serbian Film, I think I have to argue that a society beget by violence—and deliberately begetting violence—would have to entertain itself with more violence. It’s no coincidence that the timing of this film is between Rambo: First Blood Part II and Rambo III... (Read my piece about the character of John Rambo symbolizing the fall of American hegemony here.) The Cold War was nearing its end. Real violence was (apparently) subsiding.2) Chop Top calls Leatherface “Leatherface.” I don’t remember anyone actually using that moniker in the original film. Like Pinhead in the Hellraiser series—originally billed as Lead Cenobite—the name fans called him stuck.

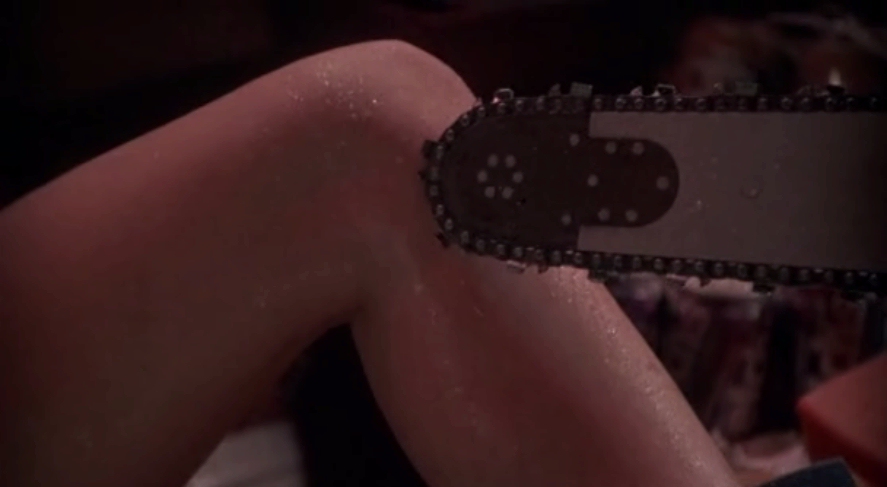

3) Leatherface’s attack on Stretch in the radio station, and her response—it takes the sexual metaphor of the killer wanting to penetrate his victims to a rather overt level. Clover (1992) writes about the scene:

At the crucial moment, however, power fails Leatherface’s chain saw. As Stretch cowers before him, he presses the now-still blade up along her thigh and against her crotch, where he holds it unsteadily as he jerks and shudders in what we understand to be orgasm. (p. 25-26)Clover leaves out some notable details—and this may get a bit... adult. Especially the dialogue. See, Lefty is caught sitting at the end of a tub of ice with beers in it. Her legs are spread, and Leatherface brings his chain saw down into the ice a few times as she screams, and makes more than a few references to God. If not for the tenor of her screams (and the presence of a chain saw, of course) it would play like a sex scene. The dialogue, though... Stretch stops screaming and gets Leatherface to shut off his chain saw by asking first if he’s mad at her, then “How good are you?” There’s an implied sexual tone to the line right away. But, just to drive it home, she repeats it with just enough pause to make it clear. “How. Good. Are. You?” Then Leatherface takes the now-still blade and puts it to her bare leg, slides it up her thigh. “Really,” she asks. “Are you really, really good?”

Then, as the blade nears her crotch, she’s less tentative. “You’re really good. You really are good. You’re the best.” (Note: Clover does mention this dialogue in a separate passage.) Metaphorically, cinematically, she has not only come onto him, she’s made him come as well. Though he then explodes in a rage, he damages stuff in the room rather than kill Stretch. And, later when she shows up in the tunnels, Leatherface actually keeps Drayton from finding her. Clover suggests, “Only when Leatherface ‘discovers’ sex in Part Two does he lose his appetite for murder” (p. 28).

As for the cycle, Clover refers to the “first phase” of slasher films, running from Psycho in ’60 to The Texas Chain Saw Massacre in ’74. She says the films in this phase are “dominated by a film clearly rooted in the sensibility of the 1950s”—that is, they owe much of their visual style to Hitchcock. The next phase, Clover says, “responds to the values of the late sixties and early seventies” (p. 26).

4) Chop Top and Drayton Sawyer call Leatherface “Bubba.” I suppose that might actually be his name.

I’d go a bit further, taking Clover’s “phases,” and say that The Texas Chainsaw Massacre 2 specifically responds to the values of the previous slasher films. The overtly sexual interactions between Leatherface and Stretch, the references to her being his “girlfriend”—it takes what was subtext and twists it into text. The question is, where to go from here? The slasher film has reached a campy climax.

After this, as we’ll see in coming days, the Nightmare on Elm Street series becomes more comedic, the Friday the 13th series becomes a little more outlandish, and when the Halloween series returns, it does the opposite—taking itself quite seriously—so much that it explains itself into one corner after another, and loses itself in the mess, only to be rebooted. The slasher genre probably peaked here. The return of Halloween served as an attempt to prop it up, but maybe we weren’t looking for the violence anymore.

Yeah, right.

Works CitedClover, C.J. (1992). Men, Women, and Chain Saws: Gender in the Modern Horror Film. Princeton: Princeton University Press.Nowell, R. (2011). Blood Money: A History of the First Teen Slasher Film Cycle. New York: Continuum.

TCM's sequels (like the Psycho sequels) were definite cash-ins, as far as studios watching the late 70s/80s horror boom and seeing it creating a market for sequelized franchises, as well as renewed interest in the classic proto-slasher films like Psycho and TCM.

ReplyDeletePart 2 at least has the honesty of seeing that it was a cash in and trying to find a new angle to approach a studio mandated cash grab sequel. The dark comedy angle (which showed itself most notably with the box art, which was the bad guys posed just like the Breakfast Club folks) at least made the film work in the context of a new take rather than recycling the first film like Part 3 did.