underneath that crazy hat of yours

I never got to the point I wanted to make yesterday. It's difficult, really, to demonstrate how Into the Wild doesn't (quite) romanticize Chris McCandless' adventure just by looking at how he leaves his parents and his sister behind. His parents are not portrayed as good people that we might care about when they hurt. We can objectively understand that they are in pain, but we just might not care (even if the film does make the effort of framing the film with the parents in pain, Billie in the opening scene, Walt just before the ending. And, Carine--she tells us that she understands her brother's choice to leave. In reality, she explicitly knew that he was going to separate himself from their parents, though she didn't know what he was going to do. In her book, she shares a letter he sent her, which included this: "I'm going to completely knock them out of my life... I'm going to divorce them as my parents."

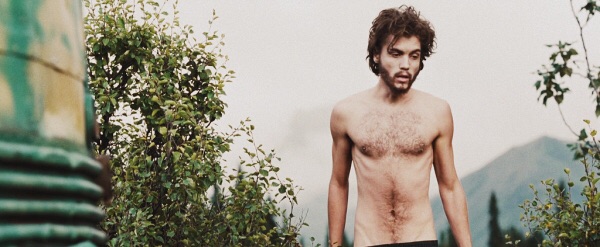

What I think really serves to de-romanticize Chris' adventure in the film is the structure of the film itself. The film offers two strands of Chris' story, running next to each other. One begins with his arrival in Alaska and continues to his death. The other begins with his graduation from college and ends with Ron dropping him off to find another ride north. The series of emotional climaxes, Chris leaving Jan and Rainey (Catherine Keener and Brian H. Dierker), Chris being unable to return across the Teklanika River, Chris leaving Ron, Chris starving--these run together to offer up multiple levels of tragedy. Since leaving his life as Christopher McCandless and becoming Alexander Supertramp, he has made a friend in Wayne Westerberg (Vince Vaughn), gained a pseudo family in Jan and Rainey, a potential love interest in Tracy (Kristen Stewart), and a (grand)father figure in Ron (Hal Holbrook). And, he does intend to return from Alaska.

Despite some theories, he did not go there to die.

Alaskan park ranger Peter Christian quite famously suggested that Chris suffered from mental illness. Christian writes:

When you consider McCandless from my perspective, you quickly see that what he did wasn't even particularly daring, just stupid, tragic and inconsiderate...Essentially, McCandless committed suicide...McCandless wanted to die (whether he realized it or not). The fact that he died in a compelling way doesn't change that outcome. He might have made it work if he had respected the wilderness he was purported to have loved. But it is my belief that surviving in the wilderness is not what he had in mind...

The tragedy is that McCandless more than likely was suffering from mental illness and didn't have to end his life the way he did. The fact that he chose Alaska's wildlands to do it in speaks more to the fact that it makes a good story than to the fact that McCandless was heroic or somehow extraordinary. In the end, he was sadly ordinary in his disrespect for the land, the animals, the history, and the self-sufficiency ethos of Alaska, the Last Frontier.

Another Alaskan park ranger, Ken Ilgunas offers a counter:

We can use many words to describe McCandless, but "stupid," "insane" or "suicidal" shouldn't be among them. To ridicule McCandless for pursuing his dream--however illogical you may think it was--is to ridicule all dreams. It's to ridicule the ancient voyages, expeditions across continents, the quest for civil rights, a colony's fight for independence, and dreams of leaping across distant planets.There are a thousand excuses not to pursue our dreams. We may have jobs, families, bills and obligations. We have fears and insecurities. We might think: What if it doesn't turn out the way I expected? What if I find out I can't do it? What if I die?

McCandless, I'm sure, asked these same questions. And that which distinguishes him from those who hate him is the fact that he had the courage to live a full life before a long one.

We define insanity sometimes simply as that which differs from the norm. At all. It's normal to be heterosexual, so homosexuality must be a mental illness. Until 1974, it was a mental illness according to the American Psychiatric Association. It's normal to be follow our society's standards, to go to school, to get a job, to marry and have kids. So, anything else must also be mental illness. Somehow it has become normal to, for example, sit in an office for 8 hours a day, 5 days a week, performing mind-numbing work that bears no link to any product. The sense of accomplishment is limited. But, that's okay because we've got television and alcohol to while away the hours we are not at work. And, if mental illness shows up, there's medication.

(There are, of course, some conditions that do require medication to balance things out, but medication, generally, is pushed far too readily and easily.)

Ilgunas points out that Peter Christian

seems to wrongly associate reckless behavior with suicidal behavior. And this is, I believe, the central defect of his argument. McCandless was, without question, reckless. But shall we presume that all reckless people are suicidal? McCandless, like his adventuring forbears [sic], beheld [sic] characteristics unique to explorers, not suicides. Was Heyerdahl suicidal for wanting to cross the Pacific in a wooden raft? Were Hilary and Norgay suicidal for climbing Everest when every capillary and muscle pleaded that they descend? Was Robert Falcon Scott, who died en route to the South Pole, and the millions of adventurers before and after him--who died in pursuit of a dream--just crazy and suicidal?

The simple answer to all of Ilgunas' questions is no. If adventuring and exploring is mental illness than it is only through mental illness that the world has become what it has become. (To be fair, I don't necessarily think we have gotten where we are at present through entirely sane means.) This country in particular, founded in violence, would not exist without the suicidal explorers who brave the Atlantic to get here.

The closest Chris gets to something like mental illness in the film might be when he leaves the homeless shelter. Just being in the city, being under a roof (nevermind that he stayed in a house while working for Wayne earlier), he sees himself civilized, dressed in a suit, clean shaven, and he runs away again. But, the real mental illness is in the city itself, allowing those homeless men and women to live on the street or in a shelter when there are rich folks who spend more in a day than some of us make in a year. Hell, Chris' parents (and presumably his sister) went on a trip to Paris just after his graduation.

(I'm reminded of Daniel Quinn's arguments regarding the homeless in Beyond Civilization... but I don't want to get into that just now.)

Mental illness, if it is present in Chris McCandless, might be that impulse to shoot that moose. More food than he could use, more food than he knows how to preserve (though he does try). But, he shoots it anyway, because, in that moment he was more like the men of the society he had departed, more Chris McCandless than Alex Supertramp.

Wanting to be free is not insanity. Wanting to venture away from the restrictions and expectations of the modern world--if you never have that impulse, then there is something wrong with you.

Comments

Post a Comment