change the world, make it better

The thing about Baby is, she is already is someone who wants to make the world a better place. Maybe despite her parents—it's a little presumptuous to think they aren't all for her plans—she wants to join the Peace Corps. The Peace Corps had only recently begun. The first group of volunteers started training in June 1961. She references monks burning themselves in protest—Thich Quang Duc famously did so June 11 1963. Right before the film starts. And, she "wants to send her leftover pot roast to Southeast Asia" (sort of) and she plans to major in "Economics of Underdeveloped Countries"—

So, it's not that Baby needs to figure out who she is. She just needs to figure out who she isn't. Notably, at the big opening show Baby is brought on stage for the magic act and she is sawed in two. A metaphor for this whole summer. She wants to be the dutiful daughter, but she's already leaning toward something else, and this is the summer that pushes her over that edge.

Just look at the costuming. From when Baby arrives at Kellerman's she dresses in clothing that shows more and more skin. Obvious, of course. But, what you probably don't think about is that in the world of the film, Baby brought these clothes with her. Maybe not the leotard-type stuff (maybe she borrowed that, and the pink with white polka dots thing she wears when "Hungry Eyes" begins is probably just her bathing suit), but the denim shorts, the tank tops.

It's worth noting, of course, that she also dresses most of the time in white or at least very light colors, and Johnny's outfits are partly or all black. The film wants us to see Baby as an innocent learning something new. But, that isn't quite true. Instead, the movie wants us—

It's important that Johnny and Penny don't need Baby's help, though. They've got plans for Penny to get an abortion. They've got friends. They seem like people who find a way to get things done. And, when Johnny finds that he locked his keys in his car, he immediately pops the top off a nearby post and breaks his own car window. He is not helpless. Which makes it all the more important that Baby involves her father in helping Penny, and admits in front of him that she spent the night with Johnny to get Johnny off the hook for theft. Johnny is just a commodity at Kellerman's. No one there sees him as a person outside the staff that dance up on the hill. And Baby.

And, notably, Johnny makes no effort to use Baby as his alibi, because he is better than that.

Jason Bellamy, Slant Magazine, 7 September 2012:

Noo Saro-Wiwa, The Guardian, 31 August 2017:

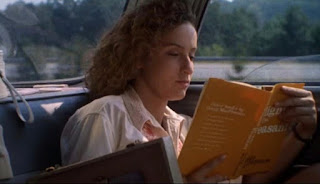

(I find it odd that Neil tells her that he is "going to Mississippi with a couple of busboys, freedom ride." With a different tone, it could be a sarcastic response to her Peace Corps plan, like he doesn’t buy that a rich Jewish girl like her would deign to do that. Except, the actor playing Neil doesn’t say it that way. He says it like he means it. His reference to busboys could be a racist sort of line, too, and right before they bring the old black guy up on stage as a token performance.)—and she is reading Gregg's MacPherson's Plight of the Peasant in the car. That book doesn't seem to be real. Which makes it not just a choice behind the scenes, but a very deliberate one.

So, it's not that Baby needs to figure out who she is. She just needs to figure out who she isn't. Notably, at the big opening show Baby is brought on stage for the magic act and she is sawed in two. A metaphor for this whole summer. She wants to be the dutiful daughter, but she's already leaning toward something else, and this is the summer that pushes her over that edge.

Just look at the costuming. From when Baby arrives at Kellerman's she dresses in clothing that shows more and more skin. Obvious, of course. But, what you probably don't think about is that in the world of the film, Baby brought these clothes with her. Maybe not the leotard-type stuff (maybe she borrowed that, and the pink with white polka dots thing she wears when "Hungry Eyes" begins is probably just her bathing suit), but the denim shorts, the tank tops.

It's worth noting, of course, that she also dresses most of the time in white or at least very light colors, and Johnny's outfits are partly or all black. The film wants us to see Baby as an innocent learning something new. But, that isn't quite true. Instead, the movie wants us—

the kids who saw this movie because our parents got past the title and thought we were getting a basic romance involving dancing and probably regretted taking us afterward—as innocents ourselves to learn something from the film. Baby is who Baby is, from the start. A couple years earlier, still in high school, she heard Kennedy talking about starting the Peace Corps and she was inspired. Watching events unfolding in Southeast Asia she pays attention, she wants to do something. And, the microcosm is simpler: seeing the plight of Johnny and Penny she wants to help. And she doesn't hesitate to speak up, doesn't hesitate to confront Robbie, and then to get money from her father when Robbie is no help.

It's important that Johnny and Penny don't need Baby's help, though. They've got plans for Penny to get an abortion. They've got friends. They seem like people who find a way to get things done. And, when Johnny finds that he locked his keys in his car, he immediately pops the top off a nearby post and breaks his own car window. He is not helpless. Which makes it all the more important that Baby involves her father in helping Penny, and admits in front of him that she spent the night with Johnny to get Johnny off the hook for theft. Johnny is just a commodity at Kellerman's. No one there sees him as a person outside the staff that dance up on the hill. And Baby.

And, notably, Johnny makes no effort to use Baby as his alibi, because he is better than that.

Jason Bellamy, Slant Magazine, 7 September 2012:

From the get-go, Dirty Dancing is throbbing with sexuality, yes, but it's hormones are distinctly adolescent. It tapes into a time in our lives when dancing isn't just a stand-in for or a gateway to sex but is a perfectly fulfilling erotic exercise all its own. Seen through Baby's eyes, the movie is dominated not just by experimentation s with adulthood, a common theme at the multiplex, but something much rarer: the discovery of adulthood.Melissa McEwan, The Guardian, 16 September 2009:

Under the guise of a teen rom-com dressed in the styles of a period dance flick, Dirty Dancing surreptitiously delivered a subversive counter-narrative to many of the things I was hearing as an adolescent girl poised on the precipice of years that adults around me fervently (and vocally) hoped would not be marked by significant rebellion or any of the foolishness associated with raging hormones.Kate Gardner, The Mary Sue, 16 July 2018:

The film openly tackles the fact that Penny's choice was nearly taken away by legislation, and that she had to turn to less than safe means to get her abortion. It does not shy away from the horrifying reality of her situation, but rather forces audiences to face it head on while luring them in with the promise of a seemingly light movie.Bree Davies, Westword, 23 April 2013:

From my memory, all I knew was that Dirty Dancing was about, uh dancing--but in truth, it's. a movie about lying to your parents, back-alley abortions and a romance marred by classist attitudes...But...

Beyond the dancing, this movie was about Baby's liberation, her desire to help a fellow woman out of a tricky situation and her will to love who she wanted to love. Baby was a feminist icon.

Noo Saro-Wiwa, The Guardian, 31 August 2017:

Baby proves that a sense of entitlement can breed a fearlessness that delivers results...And movies. And romance. Yet Roger says, "This might have been a decent movie if it had allowed itself to be about anything." It is very much about something. From Johnny's angle, it is damn the consequences, go after what you want, dance your dance (like Scott Hastings all those decades (or five years) later will do at the Pan Pacifics), and get the girl. That's simple. That's familiar. But, from Baby's angle, there's more going on. If you've got privilege, use it to make other people's lives better, but don't treat them like lesser people who owe you something, just do what's right, make things better, and keep on doing the same every time because it's right, not because it makes you a better person. The adults around Baby—her father and Max Kellerman (and his wife, who I can't even remember if her character has a name), for example—look at Johnny and the rest of the "entertainment staff" like they're nobodies. Baby does better than that. And, if we saw this as kids—I saw it when I was 11–I hope we do better as well.

Baby's is the ultimate liberal story in which adolescent rebellion takes the moral lead and drives society forward. It dovetails nicely with my belief that indulgence, when pursued responsibly, makes the world go round. Nothing unites us as a species quicker than food, love, music, and dance.

Comments

Post a Comment